The dwarf planet Ceres – long believed to be a barren space rock – is an ocean world with reservoirs of sea water beneath its surface, the results of a major exploration mission showed on Monday.

Ceres is the largest object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, massive enough to be shaped by its gravity, enabling the Nasa Dawn spacecraft to capture high-resolution images of its surface.

Now a team of scientists from the United States and Europe have analysed images relayed from the orbiter, captured about 35km (22 miles) from the asteroid.

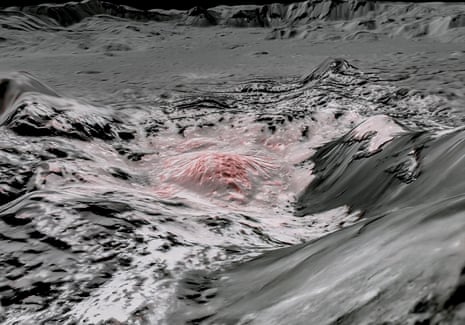

They focused on the 20-million-year-old Occator crater and determined that there is an “extensive reservoir” of brine beneath its surface.

Several studies published on Monday in the journals Nature Astronomy, Nature Geoscience and Nature Communications also shed further light on the dwarf planet, which was discovered by the Italian polymath Giuseppe Piazzi in 1801.

Using infrared imaging, one team discovered the presence of the compound hydrohalite – a material common in sea ice but which until now had never been observed beyond Earth.

Maria Cristina De Sanctis, from Rome’s Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica said hydrohalite was a clear sign Ceres used to have sea water.

“We can now say that Ceres is a sort of ocean world, as are some of Saturn’s and Jupiter’s moons,” she told AFP.

The team said the salt deposits looked like they had built up within the last 2 million years – the blink of an eye in space time.

This suggests that the brine may still be ascending from the planet’s interior, something De Sanctis said could have profound implications in future studies.

“The material found on Ceres is extremely important in terms of astrobiology,” she said.

“We know that these minerals are all essential for the emergence of life.”

Writing in an accompanying comment article, Julie Castillo-Rogez, from the California Institute of Technology’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said the discovery of hydrohalite was a “smoking gun” for ongoing water activity.

“That material is unstable on Ceres’ surface, and hence must have been emplaced very recently,” she said.

In a separate paper, US-based researchers analysed images of the Occator crater and found that its mounds and hills may have formed when water ejected by the impact of a meteor froze on the surface.

The authors said their findings showed that such water freezing processes “extend beyond Earth and Mars, and have been active on Ceres in the geologically recent past”.