NEW MARLBOROUGH — Fifty years ago, as earthlings engaged in cosmic rubbernecking to behold mankind's historical first steps upon the moon, CBS was making a giant technological leap in live television coverage.

The network's executives had turned to Douglas Trumbull, whose groundbreaking photographic effects in Stanley Kubrick's "2001: A Space Odyssey" made him instantaneously famous the year before.

The moviemaker and self-described "mad engineer," whose love affair with rockets, space and alien life began as a boy in Los Angeles and continues to this day from his studio in New Marlborough, was hard-wired for the challenge.

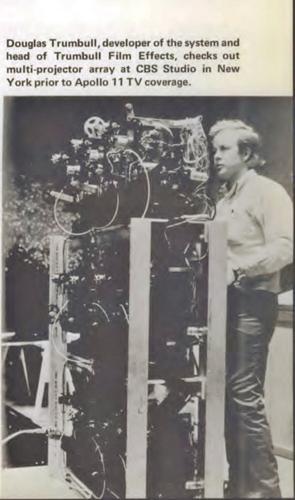

With six month's lead time and NASA's 6-inch-thick Apollo flight manual at his disposal, Trumbull devised a newfangled and ingenious graphic display system for CBS' coverage of the mission that began July 16, 1969. Of course, those were the days before computer graphics. The system, dubbed "HAL 10,000," in tribute to HAL 9000, the sentient computer system in "2001," included nine projectors capable of displaying by remote control any number of variations of diagrams and flight simulations.

It was a big technological deal perfectly suited to humankind's grandest technological moment to date: that of landing on the moon and coming back to Earth alive.

"Anything could happen," recalls Trumbull, who operated the system during the coverage. "We were to be ready for any contingency, which we were, and it was fortunate nothing tragic happened, and it worked."

He built the Hal 10,000 in Studio City, Calif., and then moved it all to CBS' midtown Manhattan "space headquarters" studios just days before Apollo 11's liftoff. With Walter Cronkite leading the coverage, producers continually turned to Trumbull's graphic projection system to help clarify in real time each phase of that complex, marathon mission that ended with the three-member Apollo 11 crew safely splashing down in the Pacific Ocean on July 24.

Trumbull's work in the broadcast has received several mentions in the many commemorations of Apollo 11's 50th anniversary, including in PBS' recent "Chasing the Moon" series. Indeed, HAL 10,000 was groundbreaking in its day. Television stations across the country would soon adapt a scaled-down version of it to enhance their newscasts.

But as Trumbull is well aware of these days, when you put his name together with "NASA" and "television studio," that makes for a fine silage feasted upon by conspiracy theorists who have long contended the moon landing was a hoax staged by NASA with Stanley Kubrick's help.

On his 50-acre wooded compound in New Marlborough, where he has lived and worked since 1987, Trumbull rolls his eyes at the mention of it.

"I think it's kind of obscene, frankly," he says of the conspiracy theories. "The amount of love and labor that went into the Apollo program is staggering. It's so staggering few people can get their heads around how complex and difficult and heroic and amazing it was.

"Some people just want to debunk it because it's over their heads," he says. "They can't understand it."

Trumbull, 77, opts to ignore the hoaxer crowd, instead preferring to concentrate on intelligent life on our planet and beyond. He grew up marveling at, and modeling his own future work upon, the engineering resourcefulness displayed in those early days of rocketry and space travel.

Flight was a theme ingrained in the family. His father was a mechanical engineer for Lockheed Martin and had a brief stint working in Hollywood, including making sure those malevolent monkeys in "The Wizard of Oz" flew their approved flight path.

When Trumbull himself was a boy, his flight was one of fantasy.

"My mother died when I was 7, and I was a forlorn kid," Trumbull recalls. "I had a fantasy life emboldened by science fiction — the books of Robert Heinlein and movies such as `Destination Moon.' "

He became enamored with illustration. He took to drawing alien planets and rocket ships and eventually parlayed his skills into a gig with NASA providing illustrations for promotional films of its space program. That led to work on the film "To the Moon and Beyond," produced by Graphic Films Corp. Shown at the 1964-65 New York World's Fair, the film caught the eye of Kubrick and the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clark.

Soon, Trumbull, at the age of 23, was off to England, working with Kubrick on "2001," an assignment that took nearly three years of his life and helped revolutionize filmmaking.

"I first just tried to make myself useful to him," he says. By the end of production, Trumbull was a visual effects supervisor credited with engineering some of the film's trippiest, most enduring scenes, including the famous "Star Gate" sequence.

Since then, Steven Spielberg, Ridley Scott, and Terrence Malick have all come calling upon Trumbull, who has famously provided visual effects for such films as "Close Encounters of the Third Kind," "Blade Runner," and "Tree of Life." He directed the films "Silent Running" (starring Bruce Dern) and "Brainstorm" (starring Natalie Wood).

From his Trumbull Studios shooting stage, workshops and production offices in rural New Marlborough, he has been "working on the future of cinema" and "the future of entertainment."

"I came to the Berkshires because it's home to a lot of creative people — writers, artists, musicians — as good as anything you'll find in LA," says Trumbull, who was awarded an Oscar in 2012 for his technical contributions to the motion picture industry.

His many projects include developing a high-resolution, 120-frames-per-second 3D filmmaking technology called Magi, which uses a curved screen that he also developed. The filmmaker Ang Lee, for one, has shown an interest.

And, indeed, he considers himself among the "serious and committed believers" in intelligent life beyond Earth. No, he's never seen a UFO with his own eyes. He'd love to, though.

He's friends with the French "ufologist" and astronomer Jacques Vallee, who served as inspiration for Francois Truffaut's character in Spielberg's "Close Encounters."

He's also working with Virgin Galactic's space tourism program. The hope is to mount cameras onto a spacecraft to provide a visceral film experience of spaceflight to the general public.

"I think it could be very socially transformative for people to see the planet from space," Trumbull says. "Everybody who goes to space comes back and says, `Wow, you just have to see the world from up there. You'll feel differently about the whole planet. You can't see borders or barriers or war or famine. Just the beautiful planet floating in the middle of nothing.' "

Planet Earth: a perfect launchpad for a career such as Trumbull's.

Felix Carroll can be reached at felixcarroll5@gmail.com.