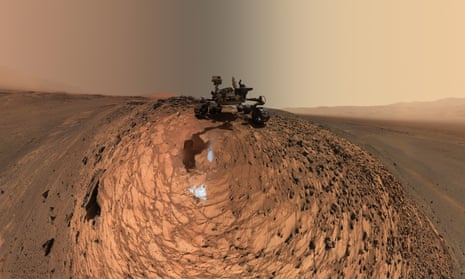

Mars

This week, Nasa’s veteran Curiosity rover discovered complex organic matter that had been buried and preserved for more than 3bn years in sediments forming a lake bed. This means that if microbial life did land on Mars, it would be nourished.

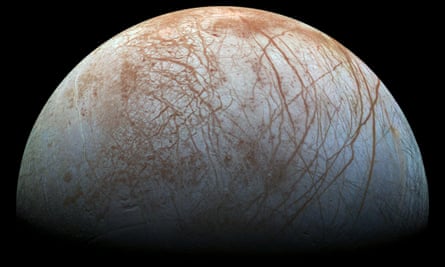

Europa

One of Jupiter’s four Galilean moons, Europa is the sixth-largest moon in the solar system. It is thought to have water oceans beneath the surface and, like Earth, an internal energy source from radioactive decay. This has led to the hypothesis that life may exist in conditions similar to that of Earth’s hydrothermal vents.

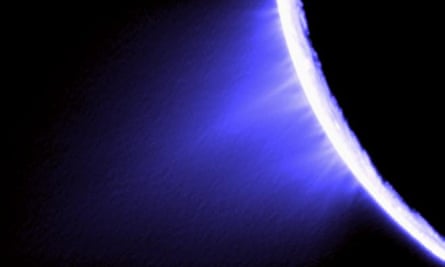

Enceladus

Saturn’s sixth-largest moon is mainly covered by ice, and ejects geyser-like plumes of water that contain nitrogen and trace amounts of carbon-bearing molecules. Robotic missions have been proposed to further investigate the moon’s potential to support microbial extraterrestrial life.

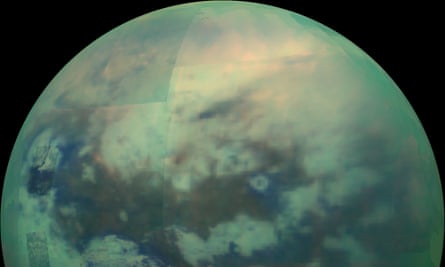

Titan

Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, is thought to have an environment similar to that on primordial Earth. It has a dense atmosphere and liquid methane on its surface. Although methane-based life forms are hypothetical, scientists have modelled conditions under which they may exist. Some experts have said that although life on Titan is extremely unlikely studying the planet could give us valuable insights into how life began on Earth.

Venus

Although the mean surface temperature of this planet is a not very habitable 462C, scientists have suggested that its upper atmosphere could tolerate life in the form of floating microbes that could feed off the carbon 30 miles (50km) up from the planet’s surface. One Nasa scientist has suggested that humans could colonise Venus’s atmosphere using lighter-than-air balloons but considerable engineering challenges – including clouds of sulphuric acid – would have to be overcome.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion