Jupiter Is Much Stranger Than Scientists Thought

The Juno spacecraft has made several close flybys of the gas giant, revealing massive cyclones—and other weird features beneath its surface.

About every eight weeks, hundreds of millions of miles away, a basketball court-sized spacecraft named Juno swoops toward Jupiter. For a few hours, Juno loops around the planet’s poles at high speed, sometimes getting within 2,100 miles of its atmosphere. It surveys Jupiter’s swirling, opaque cloud tops, and then gets flung out to the other edge of its orbit, beyond Callisto, the planet’s cratered moon.

Jupiter is surrounded by a massive magnetic field that produces belts of radiation capable of frying Juno if it wasn’t wearing 400 pounds of protective titanium. The poles are a haven from the strongest radiation, and it’s there that Juno can aim its various scientific instruments at Jupiter’s cloud cover and collect data.

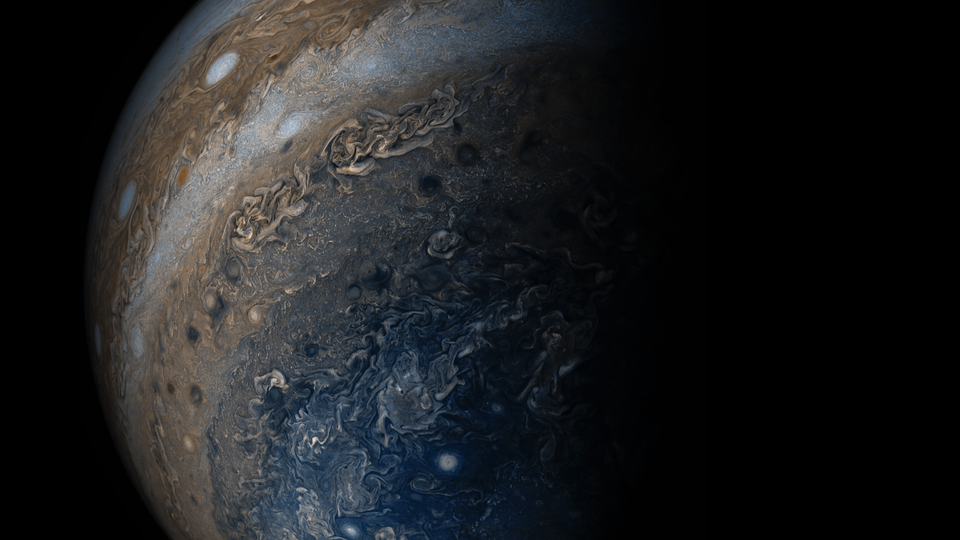

These flybys, which began when Juno entered Jupiter’s orbit last summer, have produced some stunning photographs of the gas giant’s polar regions, unlike the typical views published in textbooks over the years. They have also provided plenty of useful observations for scientists around the world, the first of which were published Thursday, in multiple studies in the journals Science and Geophysical Research Letters.

At Jupiter’s poles, Juno has observed oval-shaped features, powerful cyclones which measure up to nearly 900 miles wide, according to one of the studies in Science. The finding isn’t surprising, given how good Jupiter is at producing storms. The planet is home to winds blowing at several hundred miles per hour, and storms the size of Earth. But scientists hadn’t observed storms like this at Jupiter’s poles until Juno showed up. They were surprised by the number of cyclonic storms they observed, as well as the differences in the weather patterns on the south and north poles.

“That’s a puzzle to us,” Scott Bolton, Juno’s principal investigator, told reporters Thursday.

Juno’s observations also reveal that Jupiter’s magnetic field is about twice as strong as models previously predicted, according to the same Science study, making it about 10 times the size of Earth’s.

Other observations detected streams of electrons that might power the flashing aurorae in Jupiter’s polar regions, and provided more information about the rocky core scientists believe is at the heart of the gas giant.

The results are preliminary, and as is the case with most planetary research, more observations lead to new questions. There are plenty of more flybys to come until the end of Juno’s mission in February 2018, but what scientists have found so far will help them better understand the planet’s origins, atmosphere, and magnetism.

Juno made its sixth and most recent loop around Jupiter’s poles earlier this week, capturing still more photos of stormy weather and gathering data for future batches of research. The spacecraft is now speeding away from Jupiter, getting a break from the planet’s most dangerous radiation before it gears up for its next plunge.