The US Congress quietly passed an important piece of legislation this month. The Space Resource Exploration and Utilisation Act – yet to be signed by Barack Obama – grants American companies unconstrained rights to the mining of any resources – from water to gold. The era of space exploration is over; the era of space exploitation has begun!

While the 1967 Outer Space Treaty explicitly prohibits governments from claiming planets and other celestial resources, as their property, Congress reasoned that such restrictions do not apply to the materials found and mined there.

The bill’s timing might, at first, seem surprising – after all, Nasa, the US space agency, is almost constantly fighting against budget cuts – but is easily explained by the entrance of new space explorers on to the scene, namely the Silicon Valley billionaires who are pouring millions into “disrupting” space, Nasa, and the space programme of yore. From Google’s Eric Schmidt and Larry Page to Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and Tesla’s Elon Musk, Silicon Valley’s elites have committed considerable resources to the cause.

And while the long-term plan – to mine asteroids for precious metals or water, which can then be used to fuel spaceships – might still be a decade or more away, Silicon Valley has a very different business proposition in mind. Space, for these companies, offers the most cost-effective way to wire the unconnected parts of the globe by beaming internet connectivity from balloons, drones and satellites.

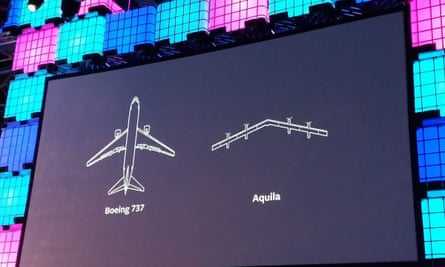

Thus, Google has Project Loon, a network of balloons floating in the stratosphere, and Facebook has been developing Aquila, a fleet of solar-powered and internet-beaming drones that can fly for months on end. Elon Musk’s SpaceX has likewise been working on a yet-unnamed powerful network of space satellites that also aims to boost global connectivity.

Space, unlike terrestrial connections with their uncertain geopolitical risks – cables, after all, can easily be cut and sabotaged – remains safe territory for the advancement of digital capitalism. The only serious challenge to America’s dominance in wiring up the globe comes from the Chinese, with state-owned or at least state-friendly companies such as China Unicom and Huawei striking connectivity deals with governments in the Caribbean, Latin America and Africa.

Thus these companies have recently agreed to build a transatlantic submarine cable that will link Cameroon and Brazil; there are other similar projects in development. Yet there are few signs that the Chinese are doing anything in space that even remotely resembles the efforts of Google and Facebook – a testament to America’s leadership in the space race.

As is typical of Silicon Valley’s doublespeak, though, its project of space exploitation is presented as yet another step in human emancipation, with Google and Facebook promising to underwrite the costs of connectivity, if only more people worldwide would start using their services.

Google has already stuck deals with the governments of Sri Lanka (where it promised to cover the entire country with free Wi-Fi) and Indonesia (where, in partnership with local telecom firms, it would beam Project Loon’s internet to smartphones – on a country-wide scale). In India, Facebook has just made its internet.org offer – users get free access to Facebook and a few other services but have to pay for anything extra – available to all customers of Reliance Communications, the country’s fourth largest operator.

These companies, however, are not just colonising space; they are also colonising time – mostly, by means of mining whatever data they can grab about our personal, social and professional lives. Digital assistants – Google Now, Apple’s Siri, Microsoft’s Cortada and Facebook’s recently launched Assistant M – all seek to produce free time for their users, mostly out of thin air.

Google’s proposition, to take one example, is deceptively simple: the more you let Google Now survey what you do – where you travel, what news you like to read, how you unwind – the more time it will save you with its suggestions and recommendations. Thus, it’s in your best interest to disclose as much as you can – otherwise, there’s little point in using the service. Hence the falling costs of connectivity, with the twin projects of space and time colonisation occurring in a mutually productive symbiosis.

The cost of delegating struggles for free time to corporations (rather than, say, trade unions or political parties) is finally becoming clearer: it makes the wilful disruptors of Silicon Valley themselves eternally undisruptable, for no other alternative social or even commercial formation can devise and run communications infrastructure of similar scale (not to mention all the data that it generates).

And then there is this other paradox of our modern living: in a world where more gathered data eventually yields more free time, an act of wilful disconnection from the global tracking apparatus becomes an extra tax on our future productivity. A little privacy is all right – but it might cost you dearly.

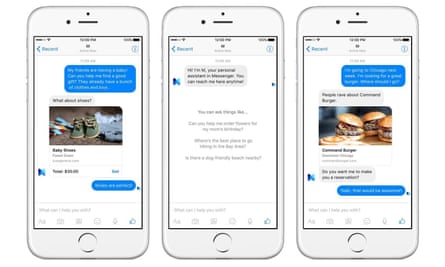

Facebook’s foray into this field with its Assistant M project indicates that there might be some extra ways to benefit from millions of poor people who have suddenly gone online, joining – wittingly or unwittingly – the global labour market.

Unlike Google Now or Siri, Assistant M – which is integrated into Facebook Messenger and resembles a chat – is not entirely virtual. Rather, it combines some advanced artificial intelligence with a team of human assistants recruited by Facebook to perform the kinds of advanced tasks that its fully automated competitors cannot currently accomplish.

It’s an interesting proposition, for it helps to deal with the creepiness factor that has beset many other virtual assistants – it’s always reassuring you are chatting with a human, not a bot – while, at the same time, allow for more advanced functionality.

The only problem, obviously, is scale – with more than a billion monthly users, it would take quite a lot of human assistants to man the service – and Facebook claims that the current human-operated stage is useful to train the next generation of algorithms.

This might be so but it’s hard not to notice that, with the injection of millions of new users in the developing world, Facebook can easily launch a strong competitor to Amazon’s Mechanical Turk service, with its low-paid freelancers competing for boring online tasks, almost overnight. This would be a clever way to scale Assistant M, enrolling the poor of India or Indonesia to help the well-off Californian hipsters order burritos or plane tickets – all for the promise of free connectivity.

“Digital divide”, it seems, is no longer about those who are online and those who aren’t. Rather, it’s about those who can afford not to be stuck in the data clutches of Silicon Valley – counting on public money or their own capital to pay for connectivity – and those who are too poor to resist the tempting offers of Google and Facebook.

To think that it doesn’t matter who provides connectivity and that, once we are all connected, all the power imbalances would naturally go away, to be replaced by a blissful harmony of global understanding, was surely one of the greatest fallacies of the last two decades. Alas, “digital divide” is just “power divide” in disguise – and the intensity and ubiquity of connectivity, at least in its highly corporate contemporary reincarnation, do little to bridge it.