The craft broke up in the clear sky 45,000 feet over the Mojave desert. During a Virgin Galactic test flight on a still October morning, co-pilot Michael Alsbury accidentally pulled a lever, prematurely deploying SpaceShipTwo’s silver scissor wings. With a sound “like paper fluttering in the wind”, the drag tore apart the fuselage and its logos for Land Rover and Grey Goose.

What was left was a flowering of red fabric in the scraggly bushes, the chute marking the site where pilot Peter Siebold floated 10 miles to earth. Alsbury did not survive.

That was almost a year ago. Today, 600 miles away, the town of Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, still waits anxiously for its space dreams to get back on track. Home to Virgin Galactic’s custom-built spaceport, the struggling community is banking on an influx of wealthy tourists eager to touch the edge of space.

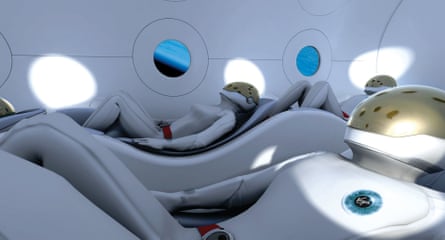

More than 700 people have bought $250,000 tickets for Virgin Galactic, which promises to take them on 2.5-hour journey 68 miles above the earth to experience a few minutes of weightlessness.

Virgin Galactic’s proposed launch site, Spaceport America, broke ground in southern New Mexico’s high desert in 2009 with almost a quarter of a billion dollars from taxpayers, $76m of which came from the two local counties that contain its 27 square miles.

The state’s support for Spaceport America is supposed to eventually enable Justin Bieber and his manager, Scooter Braun – who might be the first astronauts with only high school-level educations – to take up the gauntlet of the Neil Armstrongs and Chris Hadfields of the past era.

Since 2010, the Obama administration has cut Mars rover and spacecraft budgets, and instead prioritized space programs that rely on private companies for launch. The first space age gave its last death rattle with the shuttering of Nasa’s shuttle program four years ago.

While Neil Armstrong called the cuts “devastating”, the harbingers of this shinier future like to call this the second space age – the people’s space age, made safer, more democratic and more accessible through business. It’s a new era and a new gospel: that of the salvation of private enterprise.

Billionaire entrepreneurs Richard Branson, Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk are currently taking the future of US space exploration into their own hands. Each has launched a private space company touting space exploration for the 1%.

But since the Virgin Galactic crash last fall, the high-tech facility has sat largely vacant. A $200m boondoggle mouldering in the New Mexican desert, some have called it. Virgin Galactic, which had expected to fly tourists as early as 2009, will no longer speculate when people will be allowed to fly.

Truth or Consequences

Driving through its Georgia O’Keeffe mountains or under its aurora-clear skies, it’s easy to forget that New Mexico regularly tops the list in various poverty rankings. Americans willing to live side by side with UFO museums, the Very Large Array and the weapon to end all wars also claim the distinction of being number one in child hunger, poverty and school dropout rates.

Truth or Consequences, population 6,000 and home to the Spaceport America Visitor Center, is one of the poorest places in the state. It is a skin-of-its-teeth tourist town, and now a portal to another world.

From the Albuquerque Sunport, it’s a straight 2.5-hour shot south, through low mountains and high desert scrub. To the west, over the San Andres mountains, the troops at White Sands play their dune games. Downtown, the single traffic light is out. Past the abandoned trucks, rusted-out RVs and empty storefronts, brightly painted adobe spas advertise healing waters.

If you are confused by the town’s name, so is everybody else. Home to dreamers and gamblers, the community renamed itself in 1950 after Ralph Edwards, host of the once popular radio quiz Truth or Consequences, offered to host the program from whatever town named itself after the show. (The original name, Hot Springs, advertised the town’s plentiful natural spas.)

Edwards made good on his promise, and every May for 50 years he returned; the local museum devotes rooms to portraits of forgotten celebrities that visited the show.

Some say it got the remote resort town hooked on the limelight. When Edwards died in 2005 of heart failure, the place was left without an identity, and residents turned to the stars, as they always had.

Maybe it was their enduring faith in celebrity that prompted residents to vote in a tax hike on themselves in order to pay for Branson’s spaceport, hoping he might once again draw the big names, the parties, the bucks.

The increased taxes, adopted across impoverished Sierra County, contributed to about $5m as of 2014. Since 2009, state school budgets have been cut and an estimated $26m in necessary repairs to the town’s water system has been put on hold. There’s no more money to pay for it.

The average annual income of residents is just $15,000 per year, one third of residents live below the poverty line, and just 20% over the age of 25 have obtained a bachelor’s degree.

The spaceport is losing an estimated $500,000 per year, according to an investigation by KRQE. Among other maintenance and upkeep costs, the state spends about $3m per year on premiere firefighting services for intermittent rocket testing, despite the fact that the commercial space programs that were supposed to lease the facility have all pulled back their launch plans.

New Mexico is not the only state with a horse in the commercial space race; Florida, California, Texas, Virginia have all won bids to feather billionaire’s space dreams with financial incentives. New Mexico just happens to have jumped in with both feet, building a whole facility for Virgin Galactic and asking for little in return.

State senator George Muñoz, who has described the Spaceport Authority as “throwing money every way the wind blows”, says it’s long past time the state cut its losses and got out of the game.

“We got star-struck and made a deal,” says Muñoz. “Who didn’t want to watch space movies, right, when they were little? And who didn’t want to go into space and explore something new? And that’s what they told the people in Truth or Consequences was going to happen.”

As for the motel owners, the artists, the cooks – no one has heard of anybody living in town with a ticket up and out.

“When the Pueblo were kicked off this land,” says retiree Rich Strezo, sitting on the collapsed sofa in the Passion Pie Cafe on main street, “they put a curse on it to say that no white man would ever be successful here.”

Strezo, living out his days in a trailer on a trucker’s pension, says the town still has its attractions, including the 99-cent bowling at Bedroxx Bowling Alley on Friday nights and an art festival on Saturday. Stay awhile, he promises me, and you might find yourself picking out a $200-a-month trailer site and never leaving. Hot springs paradise and gateway to the stars.

“Spaceport America Experience visitors should be ready for an authentic experience they can’t get anywhere else!” exclaims the spaceport’s website, where I put down $50 for a four-hour tour of the “world’s first purpose-built commercial spaceport”.

Just down the street from the Passion Pie Cafe, the Spaceport America visitor center, opened in June, shares space with the library, a small exhibit on cowboy poetry and the Geronimo Trail visitor center. Inside, people are milling about, eyeing shot glasses and t-shirts, shepherded by two guides in blue jumpsuits and aviators that recall Buzz Aldrin on Apollo 11.

In a jumpsuit of his own, tour owner Mark Bleth points out the scrubbed-out outline of white numbers on the wood floors, where until a few months ago seniors played shuffleboard in the spacious 1935 adobe hall.

Residents have been arrested protesting the gutting of the senior center so that it could be leased for $900 a month to Bleth’s Albuquerque-based tour company. The original plan, sketched out for $9m by an ideas firm in Florida, called for the construction of a shiny new building – but on land that the town didn’t own and couldn’t afford to buy. The senior center was a bitter compromise, but residents last month voted to keep it as the spaceport’s visitor center.

In June, the price of the tour was lowered from $80, because that’s how you “achieve the masses”, says Bleth, who previously worked for air force intelligence and a national security contractor.

The nine other people on the tour pile into a bus, where we’re told that the trip we’re about to take contains “copyrighted experiences”, so photos are for our personal use only.

For almost an hour, we trundle along through chihuahua grassland in our creaky “rolling theater”, the video at the front telling us: “We stand at the dawn of a great second space age ... and a brighter future for us all.”

“Who would like a snack?” our guide asks, handing out peanut butter crackers. A roadrunner hurries across the road. We almost hit a calf.

As we pass a checkpoint, the video screen turns red, white and blue and displays “Access granted. Welcome to Spaceport America”, to the sound of fake futuristic doors opening and closing.

From a distance, it looks like the future – a weathered steel and glass building that appears as a blinking eye from one side and an open eye from above. The guide says the design was drawn from the Virgin Galactic logo, which includes Richard Branson’s own sky-blue iris.

The spaceport visitor center seems to have been built by someone reared on B-movies about space. The kids briefly pound away at Tetris-like video game consoles. Everyone takes a ride on the GSHock Centrifugal Trainer, which offers two Gs acceleration inside a small cage that the guides push like a merry-go-round.

Along one wall, a huge fiber-optic window separates the exhibit room from the airplane hangar, where the second SpaceShipTwo, a doppelganger of the one that crashed last October, is parked in a space built to hold five such aircraft.

If that felt like the future, everything else feels like visiting the past. Typos mar the timeline mural that places the opening of Spaceport America in line with the creation of the steam engine and early man’s use of tools.

As if to highlight what we’ve lost amid Nasa’s funding struggles, a wall is given over to an image of the dazzling Milky Way as captured by Nasa’s Spitzer Space Telescope.

With the hot hands of mid-morning on our shoulders, we exit the spaceport onto 12,000ft of silent white concrete runway.

“Kids that are being born today won’t know life without personal space flight,” says Bleth.

“This is the people’s space age. Not the government’s space age,” he continues. “In order to innovate, you have to become profitable. You can’t cut corners.”

Where will the money come from, I ask, once Katy Perry – also booked on Virgin Galactic – has had her 2.5 hours in the sky?

Bleth brings up an alternative function for the facility. He says that suborbital space travel from Spaceport America will allow wealthy sheikhs to travel extremely quickly from one location to another – like the Concorde, but faster. Why the sheikhs would want to rocket from Dubai to two-and-a-half hours south of Albuquerque, New Mexico, Bleth does not explain.

Back on the bus, the video flickers to life with quotes from corporate heads who have invested in commercial spaceflight.

“Taxpayers have less and less patience with paying for things,” says a man stressing the importance of the private sector, nickel mining and cheap extraterrestrial resources. He refers to the quarter of a million dollars you can pay for a ticket as evidence of “democratizing space”. None of them mention that the building was erected and continues to be maintained by the grace of taxpayer dollars.

One talking head says that in five, 10, 15 years, we’ll all know people who have traveled to space. It will be as common as “clean water”, says another.

The UN’s Millenium Development Goals point out that about 11% of the global population is still without access to safe water. New Mexico public radio not too long ago noted that one in three New Mexico children don’t know where their next meal will come from.

Before I leave, Bleth shakes my hand and says, “I see myself being a part of spreading the good news. Prophesying out here.”

I ask him if he’s going to space. He explains that he couldn’t afford a ticket but that there was a program a couple of years ago set up by Virgin in which you could accrue points for a trip to space based on the number of people you influenced. The program was discontinued, he says, but he’s hoping he’ll have enough points someday, and that the company will decide to let him go. (A spokesperson for Virgin Galactic could not confirm that such a program ever existed.)

I ask Bleth if he’s a religious man. He smiles in a way that indicates he won’t say more. “I have my faith, but this is also something I believe in.”

Back at the collapsing couch, Strezo tells me he’s lucky he has his pension; that times have changed and it’s hard for young people my age.

Everybody knows everybody, and Strezo acknowledges the people coming in and out with a “how’s your mother?” or “you’re looking good, kiddo”. His friend Bill comes in, tired from an odd job that barely paid him enough to cover his gas.

“There are too many people in this country,” says Bill. “People who aren’t supposed to be here. That’s the trouble we’ve got.”

Strezo shakes his head at Bill, his silvery cataracts looking past him. He says the immigration issues people complain about here are a distraction contrived to keep poor people fighting each other. “It’s the money men that try to drive you and me apart,” he says, “to make it seem like those are the issues.”

The country’s gone cynical, he says, since he was a boy almost a century ago, and no one takes care of each other like they should. Everybody’s money-hungry.

Jim Wagner, who works in hotel parts, agrees that people’s priorities have gone sour. “This county’s struggling, and we’re building a pipe dream for a billionaire,” he says, twirling an old Nokia flip-phone in frustration. “It just seems unfair.”

When I leave him, Strezo says he doesn’t know how to use the internet, but gives me the address of his trailer and says to keep in touch.

‘The risk is worth it’

After Mike Alsbury’s death last fall, Branson, looking pained under waves of easter-egg-colored hair, said to the cameras, “I truly believe that humanity’s greatest achievements come out of our greatest pain.”

“The risk is worth it. I’m sure Mike would be the first to say that”, he told CNN Money a couple days after the crash. “We know the importance of what we’re doing.”

Spaceport America has three other clients apart from Virgin who sporadically test rockets or launch payloads, but their fees – along with Virgin’s $1m lease – still don’t cover the upkeep the state has been paying every year.

The explosion of billionaire Elon Musk’s SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket in June underlined the dangers in even the relatively simple business of carrying payloads to the International Space Station, a business Spaceport America is counting on.

And with Amazon billionaire Jeff Bezos’s September announcement that his own personal commercial spaceflight company, Blue Origin, will fly out of Florida, Spaceport America’s options diminished a little further.

Richard Branson was not available to speak for this story, nor was Spaceport America CEO Christine Anderson or anyone from the Spaceport Authority. But a spokesperson for Virgin Galactic wrote to say that the company is providing “frequent support to the New Mexico Spaceport Authority’s efforts to attract more tenants and reach its full, sustainable potential”.

A press release from the Spaceport Authority in September shed some light on the progress to put the desert eye to some use. Intergalactic love story The Space Between Us will film at the facility this fall.

It will be directed by Peter Chelsom, whose titles include Hanna Montana: The Movie and Town & Country, a romantic comedy that lost $80m at the box office – one of the most notoriously expensive cinematic flops in history.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion