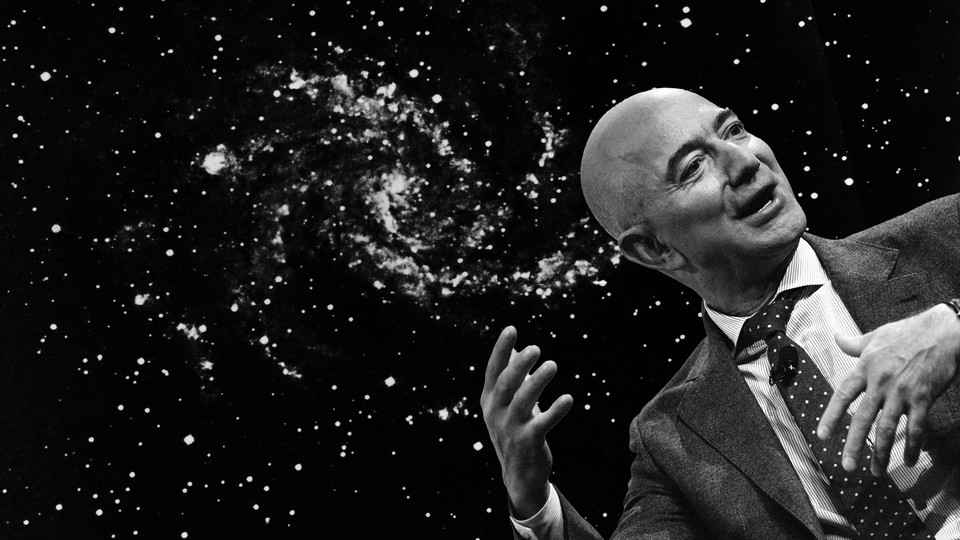

Jeff Bezos Has Reached His Final Form

The Amazon billionaire is going to fly to space this year. So might Richard Branson. Has anyone checked with Elon Musk?

Jeff Bezos founded his spaceflight company two decades ago, at the turn of the millennium. You may not have known that, because Blue Origin spent years developing its rocket technology in secret. But by now you’ve probably heard, because Bezos wants everyone to know: Blue Origin is sending passengers to space, and he’s going on the inaugural trip himself. He shared the news this week on Instagram, in a high-production video set to heartfelt music, with one dramatic, made-for-camera moment. Bezos, wearing a cowboy hat and aviators, drink in hand, smiles at his brother, Mark. “I really want you to come with me,” he says. “Are you serious?” Mark asks, eyes wide.

Their trip—what Bezos calls the “greatest adventure”—is scheduled for July on Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket, named in honor of Alan Shepard, the first American to go to space. The Bezos brothers will travel just beyond the edge of space, experience a few minutes of weightlessness, and then return to Earth in a parachute landing in the West Texas desert. In the short time from takeoff to touchdown, Bezos, the richest man in the world, would become the first person to fly on his own rocket to space.

But of course, Bezos is not the only space billionaire out there. Not to be outdone, Richard Branson is reportedly considering taking a ride on his spacecraft in July too, about two weeks before Bezos’s flight. Branson also founded his spaceflight company, Virgin Galactic, in the early 2000s. Virgin’s space plane recently carried two pilots to the edge of space, and it’s ready to fly more. (Virgin Galactic, when asked about Branson, didn’t deny the possibility.)

No word yet on whether Elon Musk, who also founded his spaceflight company, SpaceX, about two decades ago, plans to hop on a Falcon 9 rocket and beat them both. Musk has been uncharacteristically silent during this little spectacle, but he could certainly chime in. SpaceX is the only one of the three companies that has moved beyond test flights, and regularly flies NASA astronauts to the International Space Station.

This is the reality of modern human spaceflight. NASA is no longer the most exciting name in the game, and the refrain ad astra—“to the stars”—carries a bit more emphasis on the ad. Bezos wouldn’t be the first rich person to buy their way to space—the first space tourist flew in 2001, paying some $20 million for the experience—but he could easily take the ride again, just because he liked it. For two decades, these space billionaires have been talking about dreamy and urgent reasons for exploring space, but their first step off Earth is turning a visit to space into the ultimate status symbol.

When Blue Origin was founded, Amazon was crawling out from the implosion of the dot-com bubble, and Bezos, the 48th-richest person in the world at the time, bankrolled the new venture with millions of dollars from his personal fortune. Few knew it even existed until a few years later, when Bezos started buying land in Texas for a launch facility. Only in the past several years, as Blue Origin has begun to publicize its work, have more people come to associate Bezos with space travel. Two weeks before his historic flight, Bezos will step down as Amazon CEO, motivated in part by his desire to devote more time to the space business.

Bezos, a sci-fi fan since childhood, has an Interstellar-esque hope for humankind’s future in space. As high-school valedictorian, he told his classmates he wanted to save the Earth by sending millions of its inhabitants into space. He now envisions many space stations, kept in perpetual motion to produce artificial gravity, orbiting Earth. Some outposts would replicate idyllic versions of familiar cities, national parks, and landmarks. Others would contain factories and their harmful pollution. Our home planet, with its boundless beauty and finite resources, would be reserved for residential and light industrial use.

But Bezos has always wanted to go to space himself, in his own lifetime, since he was 5 years old and watched Neil Armstrong walk on the surface of the moon. Bezos has been maneuvering toward that dream ever since. In the 1990s, as Amazon grew, an ex-girlfriend told reporters that “the reason he’s earning so much money is to get to outer space.” As Franklin Foer wrote in an Atlantic profile of Bezos, a friend claimed that Bezos began bulking up—a regimen that produced his infamous muscles-and-puffer-vest look in 2017—“in anticipation of the day that he, too, would journey to the heavens.” Between the shipping and the handling, the web servers and the streaming, the sexting scandal and the not-paying-federal-income-taxes, Bezos had a loftier dream.

In that sense, Bezos built Blue Origin for himself. Perhaps he always imagined he would be one of its first passengers. Plenty of men throughout history have tried out their inventions on themselves first; Henry Ford, for example, drove the first automobile he designed. This is just the first time in history that anyone has had the wealth, power, and technology to hire people to build a spaceship for semi-personal use. Many members of Bezos’s generation dreamed of becoming astronauts as children, but most of them applied to NASA.

“I want to go on this flight, because it’s a thing I’ve wanted to do all my life,” Bezos explained in the video that featured his brother. “It’s an adventure. It’s a big deal for me.” Bezos is a businessperson, but the space-tourism business that follows this first flight, with other customers paying millions of dollars for the experience, seems almost like an afterthought. Blue Origin is auctioning off one of the seats on Bezos’s flight, and the proceeds will go to a nonprofit that the company founded to support STEM education. The current high bid stands at $3.8 million and is expected to climb this weekend, when Blue Origin turns the auction into a live bidding war.

A trip to space will certainly help rank Bezos in the public’s mind as a top space billionaire, a title so far dominated by Musk, and score him a win over his peers. And Bezos could use the bragging rights. Blue Origin is working on an orbital rocket called New Glenn—for John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth—but the company is far behind SpaceX on this front, a fact Musk rarely resists pointing out. The two billionaires have feuded about space matters for years, scuffling over launchpads and satellites, but in the past year the lighthearted tone has drained from these exchanges. Blue Origin has lost out to SpaceX on billions of dollars’ worth of government deals, including U.S. national-security launches and a coveted NASA contract to develop a lunar lander that would take Americans to the surface of the moon for the first time since 1972. When NASA announced the winner in April, Musk, ever the antagonist, piled on with a joke that Blue Origin “can’t get it up (to orbit) lol.”

Bezos, reportedly “livid,” had Blue Origin formally challenge the decision. Many had expected NASA to choose more than one recipient for the moon-landing contract, in its usual spirit of competition and strategic redundancy. The NASA administrator is at least somewhat on his side; Bill Nelson praised a Senate bill passed yesterday that preserves NASA’s contract with SpaceX but directs the agency to go with at least two companies for the lunar mission, a provision that critics have dubbed the “Bezos bailout.”

These rivalries, whether over lucrative government contracts or first-in-space bragging rights, are changing the stories we can tell about why people go to space at all. The space billionaires have their own ideas about humankind’s future—Bezos with his space habitats, Branson and his space-tourism business, Musk and his Mars city (“I’d like to die on Mars,” he has said, “just not on impact”). But these futures all start in the same way, in the straightforward but dangerous act of blasting into the sky. Only a small group of people can do that now, including the billionaires. Who’s ready to go first?