The concept of NASA's Lunar Gateway—a small outpost to be built in a halo orbit around the Moon—is about five years old.

Although a lunar space station might serve many useful purposes, the concept came about for one basic reason. Due to limitations in the upper stage of NASA's Space Launch System rocket and an under-powered propulsion system in the Orion spacecraft, these vehicles do not have enough performance to get astronauts into low-lunar orbit, and then back out of it again for a return to Earth. Thus, NASA came up with a waypoint farther from the Moon and not so deep within its gravity well.

For more than a year, as NASA has developed its Artemis plan to return humans to the Moon by 2024, the space agency has positioned Gateway as the "Command Module" where it would aggregate components of a Human Landing System and from where astronauts would descend down to the surface of the Moon.

But in recent weeks it has become clear that NASA's chief of human spaceflight, Doug Loverro, prefers to build a complete lunar lander on the ground and launch it along with astronauts into lunar orbit. This architecture, reminiscent of the Apollo Program, would bypass the Gateway for the first lunar mission. (Loverro is expected to detail these plans publicly in mid-April, according to sources.) If NASA is going to bypass the Gateway for its first lunar mission, what is the purpose of the Gateway? And with opposition from the White House Office of Management and Budget, is NASA still planning to build it?

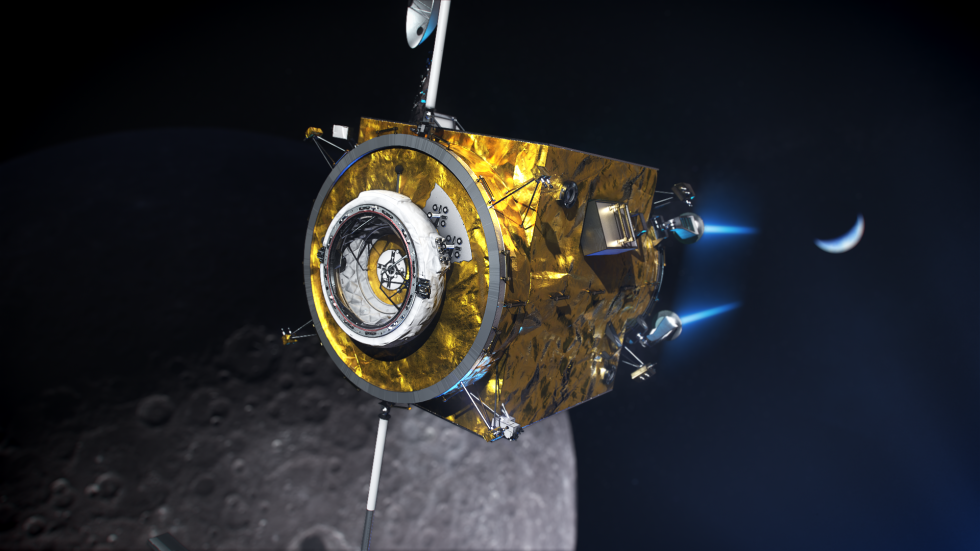

Seemingly in response to this question, NASA announced Friday that it has selected SpaceX to deliver supplies to the Lunar Gateway in the mid-2020s. The company will do so with a new version of its Dragon spacecraft, XL, launching on the Falcon Heavy rocket. This contract suggests NASA is serious about eventually building the Gateway.

To make sense of all this, Ars interviewed Dan Hartman, Gateway program manager at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, and Mark Wiese, Deep Space Logistics manager at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. A version of the interview, edited for clarity, follows.

Ars: Can you walk me through the evolution of Gateway and how it fits into NASA's plans now?

Dan Hartman: The Gateway is basically a small space station, an aggregation point to enable sustained lunar missions to the surface of the Moon, with the support of the Orion crew. And so with our configuration today, we have the Power Propulsion Element (PPE), which we have on contract with Maxar. Then there's the HALO, which is the Habitation and Logistics Outpost, being built by Northrop Grumman. Both of those are proceeding. I think we will work through both the System Design Reviews on each one of those, and we're heading toward Preliminary Design Review probably late this year. So those are progressing well.

Ars: And beyond this?

Hartman: We have the International-HAB, which we call the I-HAB, which is kind of a combination with ESA in the lead but with JAXA supplying components for that. So that is being worked on. ESA just completed a systems requirements review in the December time period, and so they're heading towards their next phase, which would be System Definition Review. And the Canadians are providing the robotic devices, which is certainly the bigger arm, and then they'll have some dexterous capability as well. They are in the final throes of going through their government, and I expect them to put a contract in place here shortly with a vendor to build the arm.

Ars: There's also the logistics element that just came out.

Hartman: We've had that in the procurement world for about a year, and that's kind of the last component of the Gateway in and of itself. And so obviously, that allows us to bring all the crew supplies up and most likely bring EVA suits up, the air, and water for the crew. And then we allocated a pretty hefty amount of research to be done within that logistics module as well.

Ars: Anything else?

Hartman: One element that we are still kind of under a lot of discussion on is the airlock, and we've reached out to Roscosmos for that. We're still working with them and so that's probably the one thing that we don't have squared away right now, as far as an agreement.

Ars: Do you have a timeline for when you'd like to get the first two pieces of the Gateway, the PPE and HALO on orbit, and maybe the first logistics mission?

Hartman: I am working toward having the PPE and HALO in place in the mid-2024 time period.

Ars: Okay. So would the first logistics mission go up then or do you think later?

Hartman: This is where it kind of gets into the question of, what is our 2024 plan? It's kind of still in the works.

Ars: You could say that. So you're waiting for Loverro's final architecture for the Artemis Program?

Hartman: Yeah, whether we go with Gateway, or direct to the Moon's surface, right? I can tell you that with the logistics mission, we're planning to have the flexibility to do it in the 2024 time period. You know how we kind of turn these logistics contracts on. You give the authority to proceed and then you start your milestones. We have time before we actually have to put authority to proceed on the very first mission. But we're going to start some early design work immediately. We've got some task orders almost ready to go with SpaceX now.

Ars: It seems to me that Dragon has some capability to really add some volume to Gateway. Can you talk a little bit about its capabilities?

Wiese: We went back and looked at some of the lessons learned from Commercial Resupply Services (CRS), and the early missions of CRS really didn't have the capability within the modules to support research. If you look at SpaceX's first two or three missions and look at where we are on SpaceX's 20th mission, the capabilities that Dragon offers for research are significantly improved, and so we took that into account.

Hartman: We're going to put payloads on the inside, and we've got quite a bit of power allocated from the Dragon XL for that. We've got upmass allocated for payloads inside and then we can also fly payloads on the outside with power and tied into their communication systems so we can get some research back down, real time on the way to the Moon, and while attached at the Moon. And then quite honestly, we don't need the logistics mission up there for six months or a year just to support a lunar mission. But we wanted to take advantage of the extra volume, the extra research accommodations, where we could keep it attached, and we could run science. Dragon also has got the automated rendezvous and docking system that they will be using on their CRS-2 vehicles, very similar to their Crew Dragon. And so, the docking system, you can come and go. We were planning to do that remotely without crew in there. And so, we think we're set up for a really good platform to conduct research for the long haul.

Ars: How is this bringing value to NASA?

Wiese: We're buying a service, right? So this is a commercial services contract built off of what we do at the NASA launch services contract at Kennedy Space Center, and what CRS has done over the years. And we really tried to get those requirements right so that we weren't driving tons of new development, right? We want to make this the best value for the government. And what you see in Dragon XL is SpaceX has taken all of the investments that they've been able to capitalize on over the years on CRS and commercial crew. And they're taking a Dragon 2 and they're expanding on that capability. They're making it more voluminous.

Ars: How are they adding volume?

Wiese: You see in the artist's rendition they put out there, they don't have to have that aeroshell, like they will when they launch Dragon on top of a single stick Falcon 9 to go to the International Space Station. Dragon XL will be inside the fairing, so they're taking advantage of that volume that they haven't had, and the fact that Dragon doesn't have to withstand the dynamic loads. Going forward we're really just expanding Dragon to be that Dragon XL capability. We're really leveraging the systems that we are using on Dragon 2 today for Crew and CRS.

Ars: In terms of internal cubic meter capacity, or whatever, is it double, or like 50 percent more than a cargo or Crew Dragon?

Wiese: Right now we're not really disclosing too much of the details.

Ars: I know Doug Loverro has talked about the importance of integrating stuff on the ground, as opposed to in space, when it comes to the Human Landing System. Have you looked at doing that with Gateway at all, like putting pieces together on the ground and maybe launching them together?

Hartman: Yeah. Loverro has stepped back and looked at the overall Artemis architecture. He's probably a few weeks from rolling all that out. So we have looked at a lot of options, I'll say, to reduce integration risks for the Gateway, and to enhance mission assurance, at the same cost. So some of those kinds of things that you mentioned are in the trade space, and I would say no decisions have been made yet.

Ars: I'm hearing that NASA headquarters is probably going to announce the new plan in mid-April.

Hartman: Yeah. So I think that they will make some decisions with the administration, and then they'll roll out all those plans. So nothing's changed from our baseline officially, I'll put it that way.

Ars: Finally, can you just maybe give me the 30-second elevator speech on why Gateway is a critical element for a sustainable return to the moon?

Hartman: Well, I think there's several things. Without question, with the Gateway, you can extend the duration of the mission, right? When you go single, I'll say direct mission to the Moon, you're limited on the supplies, either with the Lander or with Orion. With the Gateway, with just with one logistics module, we think we can extend to about twice the mission duration, so 30 days to 60 days. Obviously the more crew time you have in lunar orbit helps us with research in the human aspects of living in deep space. The more duration we have, certainly that'll help us buy down significant risk with the extreme environments that we're going to be subjecting our crews to. Because we've got to go figure out how to operate in deep space.

Obviously we'll demonstrate new hardware and offer that sustainable flexible path for our Lunar Lander system. With the Gateway, the thinking is we'll be able to reuse the ascent modules potentially multiple times. And again, if we can get mission duration beyond the 30 days, it's going to offer us some additional environmental capabilities. We think it's a tremendous risk buy down asset, not only to explore the Moon sustainably, but to prove out some things that we need to do to get to Mars.

reader comments

169