A new year means new opportunities to cross off destinations on your travel bucket list. If you’ve ever dreamt of being an astronaut and have tens of millions of dollars lying around, listen up. Starting sometime next year, the International Space Station (ISS) could be a hot new tourist destination—provided you have the cash. That’s right, as of last Friday, NASA says the International Space Station is open for commercial business and will begin hosting tourists.

The International Space Station has been in operation for nearly 20 years, soaring above the Earth at an altitude of about 250 miles. Throughout its lifetime, the orbital outpost has been home to more than 200 astronauts from 18 different countries, and is typically staffed by a crew of three to six astronauts. But the space station may soon become a little more crowded. According to NASA officials, as early as 2020, private companies will be able to send private citizens—AKA space tourists—on the trip of a lifetime as part of an initiative to help generate a sustainable economy in low-Earth orbit.

Subscribe to Observer’s Business Newsletter

The announcement was made on the floor of the Nasdaq stock exchange, in front of a group of reporters and industry partners. “NASA realizes that we need help,” Bill Gerstenmaier, NASA’s associate administrator for human exploration and operations, said during the event. “We can’t do this alone. We’re reaching out to the U.S. private sector to see if you can push the economic frontier into space.”

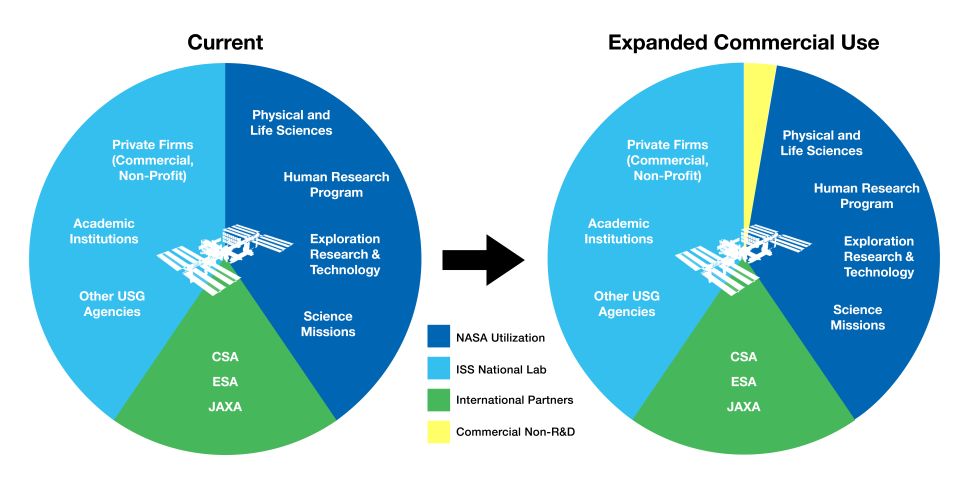

For scientists, this new opportunity means that they’ll soon be able to perform their own experiments and conduct their own research aboard the ISS without having to be limited to specific NASA programs. More than 50 companies already use the ISS for research and development purposes, sending payloads to and from the space station, but with one caveat: all commercial activities must have some sort of educational aspect or involve a technology demonstration. However, under NASA’s new policy, commercial companies can now branch out. Going forward, they will have the chance to take part in a variety of for-profit activities, including manufacturing, marketing and advertising.

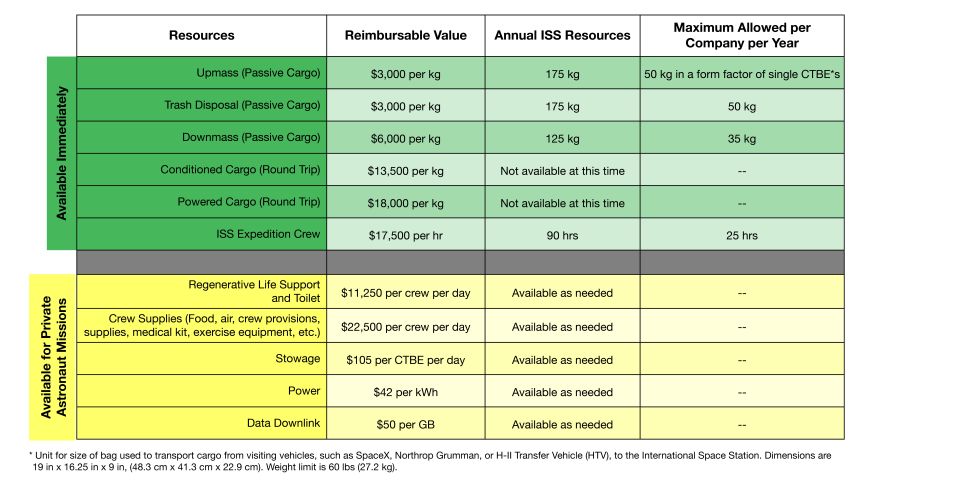

But the opportunity is also available to those who dream of space travel. Vacationing off-planet will not come with Marriott points and perks, but it will come with a hefty price tag. NASA released a full break down of potential charges, which adds up to about $35,000 a night (per astronaut), and that’s just the basics like air,

The logistics of sending up private astronauts still need to be ironed out, but one thing is clear: NASA won’t be selling space vacations itself—instead, it’ll rely on private companies to act as travel agents. Future private astronauts won’t work directly for NASA, but they will receive rigorous training (and be subject to the same medical scrutiny) that official astronauts endure to ensure that they are qualified for spaceflight. And they will be riding to space on the same astronaut taxis that official NASA astronauts take—SpaceX’s Crew Dragon and Boeing (BA)’s CST-100 Starliner. Neither of them have flown people yet; however, SpaceX completed its first uncrewed demo mission earlier this year.

Use of the space station will come with some restrictions. Private astronaut missions to the ISS will be limited to just two flights a year, and with each commercial crew capsule able to hold as many as seven people, we could see a dozen private astronauts fly per year. Those astronauts might be tourists, researchers developing products in microgravity, or even filmmakers and marketers looking to take advantage of the space station’s unique vantage point. Their stay will be limited to no more than 30 days, and the visiting crew will have specific tasks that they will be focusing on, while station keeping efforts, spacewalks, etc. will still be left up to official NASA astronauts.

NASA also says that only five percent of its resources on the station can be used for commercial activities. That means that only 175 kilograms per year of cargo can be sent to the ISS and that agency crew members can only dedicate 90 hours a year of their time to commercial activities. The companies will have unprecedented use of the space station’s facilities, which could be used for activities such as filming commercials or movies in space. But the agency says while its astronauts can take part in filming, they cannot endorse any particular project or company.

But this isn’t the station’s first foray into space tourism. Between 2000 and 2009, Space Adventures (an American space tourism company) partnered with Roscosmos to ferry seven tourists to the station. Each traveler is estimated to have paid between $20 million and $40 million to fly in a spare seat on a Russian Soyuz spacecraft, before spending one to two weeks orbiting the Earth. Those passengers included Dennis Tito, a multi-millionaire and engineer; Richard Garriott, a video-game designer; and Anousheh Ansari, an aerospace executive and the first female private astronaut.

Unfortunately, when the space shuttle program ended in 2011, so did the idea of space tourism—as the Soyuz was now the only way to and from space and every seat was needed for government-employed astronauts. But with the rise of the Commercial Crew Program, NASA and Roscosmos have both expressed interest in sending private astronauts to space, with the first private cosmonauts estimated to arrive on station in 2021.

NASA is touting its change of heart as a way to help fund other projects. During the June 7 announcement, NASA CFO Jeff DeWit said it was too early to estimate how much money NASA would receive through the new initiative and explained that the agency could adjust pricing every six months or according to demand. He went on to say that he didn’t expect the new venture to rake in massive amounts of cash, but the extra income could help mitigate NASA’s cost of operating the space station—approximately $3 to $4 billion each year—allowing the agency to invest more money in other projects.

Eventually, NASA plans on being one of many customers, purchasing time on the ISS at a lower cost than it currently shells out to manage the aging station. By turning control over to the private sector, NASA would have more money to pursue more ambitious missions, like its current goal of sending astronauts back to the lunar surface by 2024.

Agency officials think that these new policy changes are the first steps toward that goal. These new ventures will not only help stimulate an economy in space, but will also allow companies to develop and demonstrate technologies that will help enable NASA to achieve its goal of reaching the moon. It’s likely that even more opportunities for commercial activities will be available down the road. NASA executives say that these new policy changes are just the beginning and that the future depends on industry feedback.

The agency is also banking on the fact that some companies may want to build their own modules that would attach to the station. The space agency put out a call to private companies to submit their designs for such a module and expects to award that contract later this year. The agency has even made the port on the station’s Harmony module available for a commercial habitat to attach to (on a short-term basis). Any habitats that dock to this port will have access to the station’s utilities, and astronauts could potentially use the module during their stay in space.

Some commercial companies are already jumping at NASA’s new offer. For instance, Bigelow Space Operations, a space habitat developer, says it has already booked flights—carrying as many as 16 people total—on SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft, and plans to send up its own private astronauts once the vehicle starts carrying people. (Bigelow already has an inflatable module docked at the space station and is working on its next-generation habitat.)

But low-Earth orbit isn’t the only hot new tourist destination. Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin and Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic are building spacecraft designed for both researchers and tourists. However, those trips to space will be brief and more akin to a roller coaster ride than a destination, as travelers cross the boundary of space, experience a few minutes of weightlessness, then trek back to Earth. The upside? These trips come with a significantly smaller price tag—around $250,000.