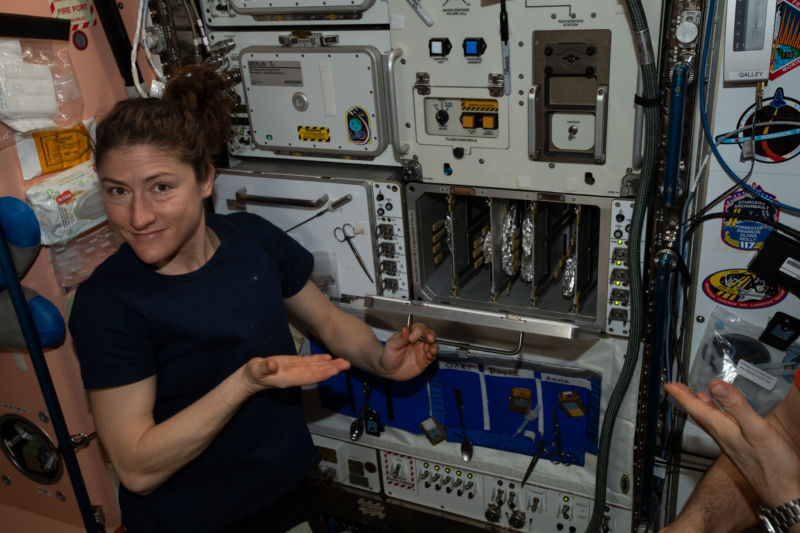

On Wednesday morning, NASA announced that Christina Koch, who is already living on board the International Space Station, will extend her mission to 328 days. By doing so, she will become the space agency's second astronaut to spend nearly a year inside the orbiting laboratory.

"It feels awesome," Koch said in a video interview from the station. "I have known that this is a possibility for a long time, and it's truly a dream come true to know that I can continue to work on the program that I have valued so highly my whole life, to continue to contribute to that, to give my best to that for as long as possible is a true honor and a dream come true."

Koch launched to the station on March 14, along with Aleksey Ovchinin and Nick Hague. As a result of the schedule adjustment, she is now expected to remain in orbit until February 2020, when she returns in a Soyuz spacecraft with NASA astronaut Luca Parmitano and Roscosmos cosmonaut Alexander Skvortsov. By doing so, Koch will set a record for the longest single spaceflight by a woman, surpassing the 288 days NASA's Peggy Whitson spent in space from 2017 to 2018.

Her mission will almost match the duration of NASA's Scott Kelly, who spent 340 days in space from March 2015 to March 2016. Although this was not 365 days, it was long enough for NASA to market Kelly's flight as a "One-Year Mission." By contrast, Koch's flight is being characterized as an "extended" stay on board the station, where increments typically last about six months. Another NASA astronaut, Andrew Morgan, will also spend about nine months on the station, from July 2019 through next spring.

Health effects

Whatever it's called, Koch's stay in space should be long enough for NASA to collect additional data about the threats of long-duration flights on astronaut health and performance. An exhaustive study of Kelly and his twin Mark, who remained on Earth, raised some troubling concerns about DNA damage and cognitive decline during the long-term flight.

With a third and fourth US mission extending beyond 250 days, NASA scientists have said they hope to better understand these threats and how the human body can adapt and respond to the challenges of microgravity. Researchers also hope to devise counter-measures to the effects of weightlessness so that astronauts visiting other worlds, such as Mars, are healthy when they reach the surface.

These concerns have led some spaceflight experts to say NASA should find better or faster ways to send humans to Mars, instead of the current six- to nine-month trip using existing technology. Some have posited that NASA should devise spacecraft that can produce artificial gravity, although the agency currently has no projects in this area. Others have said the journey must go faster, with better propulsion.

To that end, NASA has recently restarted a nuclear-thermal propulsion program at its Marshall Space Flight Center. A faster trip would mean less time in space and exposed to weightlessness and deep-space radiation, as well as healthier astronauts both for their exploration activities and later in life after they return to Earth.

reader comments

224