Dr Carrie Nugent is a 32-year-old geo- and space physicist who specialises in asteroids. Her new book Asteroid Hunters – published by TED Books and accompanied by a talk – answers all our questions on these small, mysterious objects that travel between the planets. Her day job is spotting and tracking asteroids as part of a Nasa-funded research team at the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center at Caltech in Pasadena. She is also the host of a weekly podcast called Spacepod, in which she interviews a space explorer about our universe.

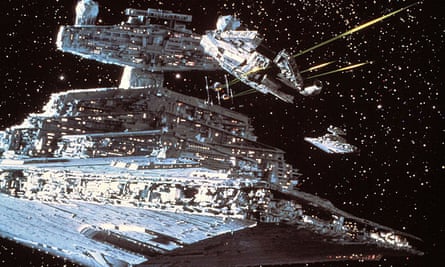

In the book, you note that much of the layperson’s knowledge of asteroids comes from Hollywood movies. Notably the scene in The Empire Strikes Back where Han Solo flies the Millennium Falcon – against C-3PO’s advice – through an asteroid field in a dogfight with TIE fighters. So that film is not especially realistic then?

It’s not. I love it anyway, but it’s very different from the asteroids in our own solar system. It’s much more dense. If you were to stand on an asteroid in the main belt of asteroids between Mars and Jupiter in our solar system, you might be able to see one or two asteroids in the sky but they would be very far away and very, very small. So you wouldn’t have this dodging-through-tons-of-rocks business you get in the movies.

Asteroid fields don’t really exist?

Maybe they do someplace else. Maybe in a galaxy far, far away, but it’s not something we’ve observed in our own solar system.

And then there were the two films in 1998: Armageddon and Deep Impact. While the events they depict are not especially realistic, you suggest they had a strange impact: they made us think about what would potentially happen if an asteroid did collide with Earth.

Absolutely. The more I think about it, the more I think I owe my own job to those two movies. Because despite the fact that they weren’t intended to be scientifically accurate, they did do a good job of communicating the hazards to people. If I go and buy a coffee and somebody asks me what I do, I’ll say, “I find asteroids.” And the first thing they always do is make a Bruce Willis joke or they are going to bring up Armageddon. And it’s great because my tiny, obscure job is on their radar. They understand immediately what I do and the importance of it.

What are the risks of a meteorite – as space rocks are called when they fall to Earth – causing serious damage?

Certainly what happened to the dinosaurs was not good – that was a terrible day for the dinosaurs, very sad. But I have to say, there are a lot of threats we face as people and, as someone who lives in Los Angeles, I’m personally more likely to die from driving on the freeway than I am from an asteroid, so you have to put that risk in perspective.

The New Scientist reported research that speculated that millions could die if an asteroid came down over a city. Or that a tsunami would kill 50,000 people in Rio de Janeiro if it landed in the sea off the coast of Brazil. How likely is that?

An asteroid impact in the worst-case scenario is a terrifying thing. It seems very uncontrollable: in popular culture it’s often a metaphor for human powerlessness over the world. But when you actually look at the problem and you look at statistics, you realise that we can find asteroids, and we can predict where they are going incredibly accurately. That’s kind of unique for something that’s a natural disaster. And, if we had enough warning time, we could actually move one away. It’s a solvable problem.

And these include firing a nuclear missile at the asteroid?

Certainly. I interviewed Lindley Johnson who’s got the coolest title in the world: planetary defence officer. He makes the point that nuclear is something that’s being considered, but he also says that it’s a last resort. One thing I found surprising is that the most effective thing might just be to get out of the way. If it’s a small asteroid – and depending on where it’s going to come down – you might just want to evacuate. In the same way you would deal with a flood.

So, to clear this up, the dinosaurs were wiped out by an asteroid?

There are a lot of other theories that have been put forth, but when talking to palaeontologists that does seem to be the leading theory.

What about the meteorite that came down near Chelyabinsk in Russia in 2013? It caused hundreds of small injuries, mostly from shattering glass, but no fatalities. No one saw that coming…

Yes, but that was a very small asteroid. So currently the goal is to find over 90% of the asteroids 140 metres across and bigger that get close to Earth. That’s the priority right now. The one that came down over Russia was only about 19 or 20 metres across. And even that is something that doesn’t happen very often. Objects of that size, only every 100 years or so.

And there’s Ann Hodges, who was hit by a meteorite in Alabama in 1954. Is she the only person that’s happened to?

She’s the only American in recorded history to be hit. It’s hard to verify exactly how rare it is, but you are far, far more likely to win the lottery. She was taking a nap on the couch with blankets over her and I always really identify with Ann because I love taking naps on the couch and I always think about her. The meteorite came in through her roof and it bounced off her radio and then hit her on the side, and the blankets protected her a little bit, so it lost a lot of energy coming in, which left her relatively OK.

Speaking of cool job titles, what does an “asteroid hunter” actually do?

Basically, asteroids look just like stars and the only thing that differentiates them from stars is that they move in the sky. So what you do is take a picture of the sky and then wait a little bit and take another picture of the sky, and see what’s moved. But I mean, I work in an office building, I have an office mate, I just got a window, I’m really excited about that, Thursday donuts are the best… It’s kind of an office job in some senses, which a lot of people are surprised about.

You have an asteroid named after you: the 8801 Nugent. What’s it like?

Ha ha! It’s pretty awesome, I have to say. I don’t have a good sense of what it looks like: I’ve seen it in images but it’s just a little point of light, it looks like a star. I was so honoured when that asteroid was named, but it’s hard to get a big head about it when you realise there’s an asteroid called 95962 Copita, which was named after an albino gorilla. It was a very loved albino gorilla, but yeah.

What are your favourite asteroid names?

Our team has named a couple of asteroids: 316201 Malala after Malala Yousafzai and one after Rosa Parks, that’s 284996. And there’s one named after Harriet Tubman: 241528. They are all amazing women and it’s really cool to honour them in this small, super-obscure way.

More than 725,000 asteroids have been discovered. As percentages go, what proportion of them do we know about?

When it comes to the biggest asteroids, we have discovered well over 90% of the 1km or larger asteroids that get close to Earth. And then that fraction goes down as we get to smaller sizes. I think that we could find all the potentially hazardous asteroids within my lifetime and I think that would be a great accomplishment.

So you’re helping people?

Yeah, in a very remote way. There’s a lot of problems in the world and this is one small thing that people are working on fixing and I’m going to keep working on this. And I’m really glad that other people are working on things like growing the food I eat and making the vaccines that keep me healthy.

Asteroid Hunters by Carrie Nugent is published by TED Books (£8.99); her podcast is at listentospacepod.com

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion