Congress loves to set grand goals for NASA. During a full committee hearing Thursday, one member of the House Science Committee said the agency should send humans to Mars in 2033. Another member upped the ante and said 2032. And another member later said he hoped to hear that NASA could even do it during the 2020s.

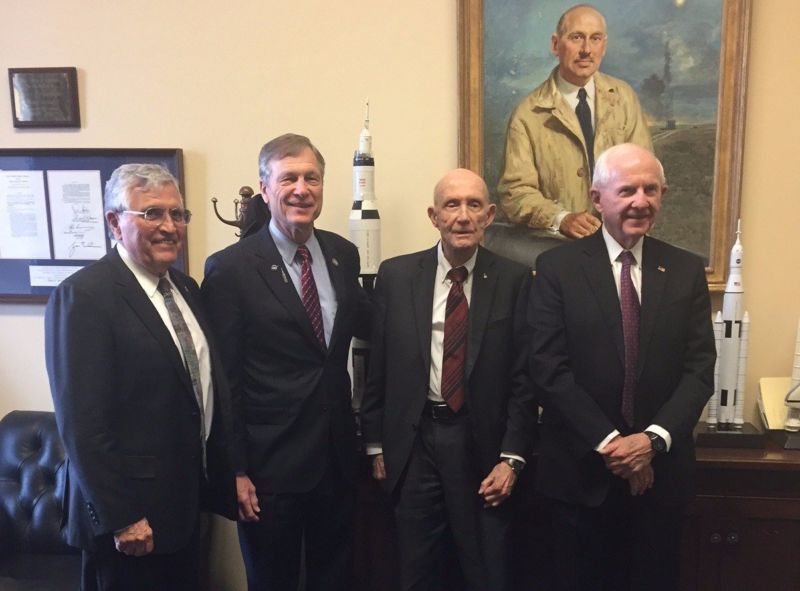

It was almost as if none of these US representatives had been listening to the expert panel called to testify on NASA's past, present, and future exploration plans. While the panel, including two former Apollo astronauts, generally agreed that NASA was on the right track with its Space Launch System rocket and Orion spacecraft, the majority felt like the agency simply didn't have enough resources to complete a compelling exploration plan. That is, NASA might have some of the right tools to launch and fly to destinations in deep space, but it doesn't have the resources to actually land on the Moon, to build a base there, or to fly humans to the surface of Mars for a brief visit.

One of the panel members, Tom Young, a past director of Goddard Spaceflight Center, said the space agency's budget is "clearly inadequate for a credible human exploration program." He said hard choices would have to be made within NASA's existing budget to actually get things done. If NASA were to continue on its present course, Young said, Congress will call a similar hearing ten years from now and lament the lack of progress toward any goal. "You'll all be saying what a disappointing decade we've had."

The budget

NASA's annual budget is about $19 billion. Slightly less than half of that is spent on human spaceflight. About $5 billion goes toward the International Space Station, including development and operations of cargo and crew missions to the laboratory. Additionally, NASA spends another $4 billion on exploration, primarily the development of its Space Launch System rocket and Orion spacecraft.

Tom Stafford, a four-time astronaut who commanded the Apollo 10 mission, testified that at present NASA only "talks" about going to Mars, rather than taking concrete steps to get there. While he praised the SLS rocket for its heavy lift capacity, he criticized a level of funding for NASA that allowed the agency to only fly it once every few years. "We certainly need the SLS, but equally we need a space program designed to make good use of it," Stafford said.

What would constitute a budget that makes good use of the SLS rocket? In his remarks, Harrison Schmitt, a veteran of the Apollo 17 mission to the lunar surface, said that instead of the roughly $9 billion NASA now spends on human spaceflight, it needs more than double that—$20 billion annually—for a meaningful human exploration program. As part of a plan that includes private investment, Schmitt sketched out a timeline that included lunar landings in 2025, lunar settlement in 2030, lunar mining in the 2030s, and a Mars landing in 2040. "If you decide you’re going to have a deep space human spaceflight program, that needs to be the focus," he said.

Most of the participants agreed that if NASA was serious about sending humans into deep space, into lunar orbit or beyond, it needed to end its financial commitment to the International Space Station as soon as possible and apply those funds toward deep space exploration. The agency is committed to supporting the station through 2024, though it has begun tentatively exploring the possibility of handing off control of its part of the station to private investors.

An alternative?

What was not articulated during Thursday's hearing was an alternative to NASA's proposed means of exploring deep space. By using the SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft, the agency is falling back upon an architecture it employed during the 1960s to explore the Moon. It is a tried and true means of spaceflight, but it is also likely the most costly route and perhaps not the most prudent one in an era of tightening budgets and newer technologies.

But it is not the only pathway to deep space today. Two private companies, SpaceX and Blue Origin, are developing heavy lift rockets that may be mostly reusable, which could shave significant costs from any lunar exploration program. Another company, United Launch Alliance, is developing an in-space transportation system between Earth and the Moon built around a reusable upper stage known as ACES.

But Thursday's hearing paid no attention to these ideas. It included three Apollo-era figures who were familiar with the older exploration architecture as well as NASA's former chief scientist, Ellen Stofan, who largely served to defend the agency's Earth Sciences programs. At the outset, the House Science Committee's chairman, Lamar Smith, said of the hearing's purpose that, "Presidential transitions offer the opportunities to reinvigorate national goals. They bring fresh perspectives and new ideas that energize our efforts." By the end of the hearing, however, it wasn't clear whether any fresh perspectives or new ideas had actually been brought forth.

reader comments

82