In 2010, I gave Virgin Galactic a five-figure downpayment. In 2014, Virgin's spacecraft crashed in the desert, killing one of its test pilots. I'm not worried. I'm still training.

On a blindingly bright January afternoon in 2010, I went to my bank to get a cashier's check for $20,000. It was my birthday, and I was buying myself the present I'd been waiting for my entire life: a trip to space.

This fat chunk of cash would become a 10 percent downpayment for a ticket aboard Virgin Galactic, billionaire Richard Branson's bold plan to hurl ordinary humans into space. To do this, Branson plans to use rocket planes that can carry space tourists 62 miles up and travel at three times the speed of sound. Ninety days before my trip, I'd need to pay the remaining $180,000. That's $200,000 for a five-minute sojourn beyond Earth's stratosphere.

Walking out of the bank, I tried not to think about the financial side of things—how I would need to decimate my savings account and my 401k to afford those few glorious minutes. It would be worth it, I reminded myself. That stomach-curdling arc would be the fulfillment of a dream I've carried with me since I was a boy watching Neil Armstrong take humanity's first step on another world.

It's been almost seven years since I bought my ticket—No. 610. But I'm not just idly waiting for my space ride. I'm preparing.

Astronomical Dreams

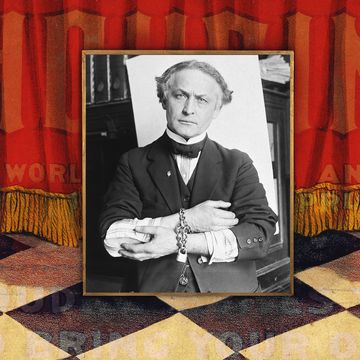

In my two decades of covering big personalities and boundary-pushing adventures, I've accomplished every terrestrial thrill one could hope for: Driving a Bugatti at a blistering 253 mph, skiing to the South Pole, swimming at the North Pole without a wetsuit, diving 1,000 feet below the Atlantic in a submersible, and climbing the Matterhorn.

Only the final frontier remains. And it's been a long time coming.

As a kid, armed with a halfway-decent telescope, I gazed with reverence at the moon's craters and Saturn's rings from our backyard near Washington, D.C. On weekends my father and I built and launched model rockets. On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong's and Buzz Aldrin's first steps on the moon planted dreams of space into my nine-year-old mind. The United States just landed on another planet and brought back men (and rocks) safely. It was an incredible feat of daring and engineering, and it gave me hope that in my lifetime I could go to space, too.

What happened next wasn't quite so encouraging. After the last moon shot in 1972, NASA's space exploration efforts pivoted toward SkyLab, the space shuttle, and then the International Space Station. NASA sent amazing probes to the far reaches of the solar system, but those were just machines—not astronauts. Today, with the space shuttle retired, the U.S. can't send a man to space without renting a seat on a Russian spacecraft. At the height of the Cold War space race, nearly 5 percent of the U.S. GNP was spent on space exploration. Now, it's less than 1 percent. NASA's funding—and my hopes going to space—were both on a sloping trajectory.

Then came the billionaire Branson, with a dream like mine and the money to make it happen. He announced in 2004 that his company was investing $100 million to hire dozens of engineers to build rockets for space tourism. And suddenly my lost dream seemed possible.

More than a decade later, Branson isn't the only one in the space tourism game. Blue Origin, headed by Amazon's Jeff Bezos, is a private company with skyward ambitions. Other firms like XCOR Aerospace and Armadillo Aerospace are interested as well. But Virgin Galactic's vehicle model is the only one testing with humans (so far). In 2004, VG's SpaceShipOne—built by legendary spacecraft-maker Burt Rutan—became the first and only non-government rocket to put men into suborbital space. SpaceShipTwo, the next-generation vehicle that will be used for ticket holders like myself, is a scaled-up version of SS1, designed to carry eight humans instead of only three.

One day, I will be on one of those eight-person flights, paying roughly $40,000 per space minute—and I want those precious seconds to count.

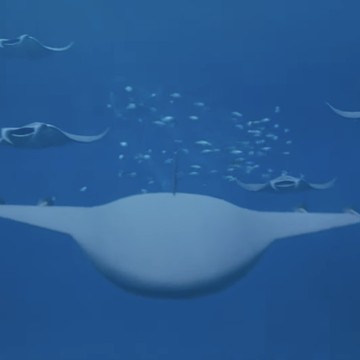

How To Become Weightless

To be the best amateur astronaut I could be, I journeyed to the far ends of the Cold War. First stop: Moscow, where they'll let you pay $5,000 to experience a few moments of zero-G flight.

Perhaps you're heard of the vomit comet, the plane that plunges into deep dives to simulate weightlessness for its occupants. Russia's version, used to train its cosmonauts, is an old cargo plane called the Ilyushin 76. This aircraft is no sleek modern jet. Climbing into the cargo area feels like being tossed back to the 1950s, with splotches of drab touchup paint on the walls and frayed cushions on the floor. Upfront, all the controls are analog. It's a plane out of time.

The aircraft climbs to 35,000 feet, then takes a controlled 40-degree plunge for about 30 seconds. During that half-minute window, passengers are completely weightless. The plane then pulls up at about 25,000 feet and climbs again. Passengers alternate between weightlessness and climbing for a total of 10 parabolas. All in all, the entire flight takes about 90 minutes.

On average, a quarter of fliers typically become ill from motion sickness during this zero-G training. To prepare for unwanted stomach gymnastics, I took some dramamine and ate a bland breakfast at my Moscow hotel just to be safe. This needed to a vomit-free excursion.

After climbing almost seven miles above the Earth, we started our first dive. Things didn't quite go perfectly on our first go-round—thinking I had to use force, I pushed off the floor and slammed my head into the aircraft's ceiling. Once I shook off the shock, I looked around. I was weightless.

Without the usual tug of gravity, you quickly learn that the force and angle of what was last touched determines your speed and trajectory. This isn't like being in a swimming pool; there's no way to correct yourself. During one decent, I fumbled with a small bag and it got away from me. My first instinct was to breaststroke toward it, which, as you might expect, accomplished absolutely nothing. The bag slowly drifted away harmlessly, bouncing off the wall.

We then did flips. The strapped-down technicians tossed us around like footballs. We opened bottles of Evian and tried to catch the water marbles in our mouths. By the last dive, though, everyone was looking a little green. My dramamine and bland breakfast saved the day. Three of my fellow travelers were not so lucky.

The Waiting

The Virgin Galactic waiting list is a weird club to join. I know that I'm on a list with A-list astronaut wannabes like Angelina Jolie, Brad Pitt, Stephen Hawking, Tom Hanks, and Lady Gaga, but also with names you'd never recognize—people with a dream of the stars and enough cash to R.S.V.P.

Virgin keeps us in the loop about its progress, but also treats us all like VIPs. We get annual holiday gifts from Branson, like silver SS2 cufflinks or a VG flight jacket. Another year it was an official personalized piece of metal for our wallets, an I.D. card for future Virgin Galactic tourist-anauts.

Despite having snared a spot on the exclusive list, I still find myself weirdly jealous of millennials. I know, I know. I should be grateful; most people haven't the means to make this journey. But what will be most likely a once-in-a-lifetime experience for me won't be that for many younger people.

As space tourism evolves and flight frequency increases, prices will come down. Think of the airline business in its early stages. Once upon a time the "jet set" were so named because only the wealthy could afford to fly. Now loads of people jet home for the holidays. It's likely that the next generation will fly for a fraction of today's VG going price, which has only climbed to $250,000.

Simulating Space

Having experienced the sensation of weightlessness, it was time to come back stateside. Jetlagged and giddy, I started planning my next training session, this one a little closer to home.

At the NASTAR Center in Southampton, PA, a giant centrifuge prepares astronauts to handle the disorienting G forces experienced during takeoff and reentry. This facility, built in 2007, is a replacement for the nearby Johnsville centrifuge where NASA trained John Glenn for his historic flight into orbit. This sleek machine looks like a giant clock with you strapped to the end of a huge second hand—only it goes much, much faster. My group, all of whom had booked tickets on Virgin Galactic, made this pilgrimage to Pennsylvania to spend $3,500 on two days of tests.

The first part of its program involves classroom instruction coupled with G-force testing in its centrifuge. The classroom explains the concept of G Force, and the types we would experience on takeoff and reentry. In the centrifuge on the second day, a simulated film would recreate the stunning views of our blue sphere we call home as we climb and fall in the simulated spacecraft.

The group quickly discovered that G-forces actually come in different shades. There's "Gz," a force that pushes down on your head during a vertical launch. Then there's "Gx," a force perpendicular to your chest that pushes against you as you re-enter Earth's gravitational embrace. Our first spins tested response to sustained Gz, around 3.5 Gs, for 15 seconds at a time. To handle that, we practiced clenching our glute, abdomen, and leg muscles to keep blood circulating to our brains. We also used the "hook" maneuver, a back-pressure breathing trick used by high-altitude mountaineers, to force air into our lungs. These two techniques fight against what astronauts call "graying out," or losing color and peripheral vision because of blood loss to the brain.

Now, to tackle those Gx forces. For these, we practiced breathing slowly and shallowly, as if through a straw, which is what breathing feels like under the immense pressure of reentry. We began things slow, 3.5 Gs at first, then ramped up to 6Gs for 15-second intervals. For comparison, the highest G-force of any roller coaster in the world barely eclipses 6Gs—and for good reason. Six Gs is a lot of pressure. If you weigh 200 lbs., it feels like a 1,200-lb. pile of bricks planted squarely on your chest.

Then we experienced a close approximation of what our five-minute-long Galactic flights would be like. I found myself instinctively doing hook breathing and tensing muscles as the rocket motor fired and the craft accelerated to over Mach 3, wracking me with Gz. Then came utter peacefulness upon engine burnout, with the craft still climbing in a gentle arc and reaching an apogee of 370,000 feet within the centrifuge simulator.

Sure enough, there was Earth, simulated in the portal window, beautifully curved with a thin, electric-blue atmosphere. Overhead was foreboding blackness. When the altimeter started dropping, there was no sensation. But as the atmosphere below thickened, Gx forces kicked in and before long it pushed down with six times my bodyweight.

So long to the serenity of space.

The Crash

As I was globetrotting to have my guts pounded with G-forces and my body launched through the air, Virgin Galactic was busy scaling up and testing higher and faster flights with SpaceShipTwo. The program started with several unpowered glide flights, then started flexing its engines. On April 29, 2013, the SS2 passed Mach 1. Branson sent all of us patches that had flown on the excursion. But then, on Halloween day in 2014, my growing optimism morphed into despair.

During its fourth powered test flight, SS2 suddenly broke apart in mid-air, killing copilot Michael Alsbury and badly injuring pilot Pete Siebold, who was thrown from the craft. All had been going according to schedule over the Mojave desert before the craft inexplicably fell from the skies. A lengthy investigation by the NTSB concluded that the accident resulted from pilot error. Alsbury had dislodged the reentry-feathering device on the way to Mach 1, which would almost be like slamming on the brakes at 200 mph in a supercar.

When I heard the news, it landed like a gut punch. I considered the situation carefully, and while upset by the news of another life tragically lost in humanity's push toward the stars, I decided I was staying put. From my early days of watching the dangers of the space race from my TV, and from my risky terrestrial adventures, I knew things like this could happen. I had lost friends on mountains and in race cars. Had this crash been on a commercial flight, full of eight fellow Virgin Galactic ticket holders, I might have pulled out entirely. But when testing an experimental spacecraft, strapped to powerful rockets, accidents can happen. It seems almost every other passenger felt the same. Fewer than 3 percent of ticket holders asked for refunds.

At their most basic, spaceships are nothing more than a controlled concoction of steel and explosives. Astronaut Kathryn Sullivan, the first American woman to walk in space, once put it to me best: "This business consists of riding bombs. If you do absolutely everything right, you can marshal the energy to do something astonishing...If you do even a few things wrong, it's going to act like a bomb."

The people on the Virgin Galactic waiting list are avid lovers of space. As such, they, and I, are familiar with space exploration's greatest achievements and also its most disheartening disasters. For every successful moon landing or space mission, there's a Challenger or a Columbia and names like Vladimir Koramov, Christa McAuliffe, and Michael Alsbury who've given their lives while exploring space.

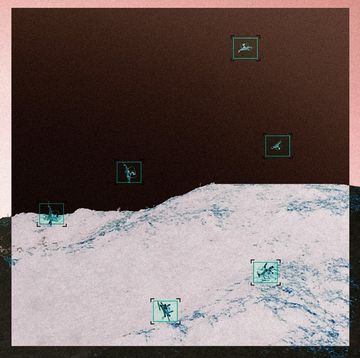

Just Go For It

In August 2016, a newly built Virgin craft called VSS Unity got FAA commercial flight approval and recently began glide flight tests, which it passed this month with flying colors. Learning from tragedy, Virgin Galactic added a locking device for the feathering system. With any luck, ticket holders should begin flying in 2017, according to VG test pilot CJ Sturckow. Branson and his family are likely to be the first of many.

Since I will be on the 100th or so SS2 excursion, my flight should happen before the end of 2019. During the seven long years I've already been on the Virgin waiting list, friends have often asked me about fear. I try not think about it because if I did, I'd be out of a job. So I like to ask other people who've pushed the limits.

Alan Eustace, the parachute world record-holder who in 2014 jumped from a gas balloon 135,890 feet above Earth, told me this: "I have a really strong belief in technology. If we tested extensively, if we understand the limitations of a particular technology, then I believe it's going to work… When you get on an airplane, you don't ask if it is going to fly.'"

When you have the opportunity to join the ranks of the brave men and women who have left this blue globe before you, you don't ask questions—you just go for it.