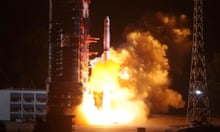

At 8pm Beijing time on 25 June this year the tropical darkness over China’s Hainan province was temporarily banished by a blinding orange light. Accompanied by the thunderous roar of engines, a 53m-tall rocket pushed itself into the sky.

An increasing number of Chinese rockets have launched in the past few years but this one was significant for three reasons. It was the first launch of the new Long March 7 rocket, designed to help the Chinese place a multi-module space station in orbit. It was the first liftoff from China’s newly constructed Wenchang launch complex, a purpose-built facility set to become the focus for Chinese space ambitions. And it was the first Chinese launch where tourists were encouraged to go along and watch.

For a space programme that has long been shrouded in secrecy, it’s a major step. The Wenchang complex has been designed with large viewing areas, and in the sultry heat of that June night, tens of thousands of spectators stood cheering as the rocket began its 394km journey above the Earth and into orbit.

“China is developing very rapidly into one of the major space players,” says Fabio Favata, head of the programme coordination office at the European Space Agency’s (ESA) directorate of science.

China launched a pioneering “hack proof” quantum communication satellite, called Quantum Experiments at Space Scale, on 16 August from its older Jiuquan launch centre in the Gobi Desert. This is the first large-scale satellite designed to investigate the weird quantum phenomenon called “entanglement” that so unnerved Albert Einstein he once called it “spooky”. In addition, China is preparing to launch another new rocket design, a new space station, an X-ray telescope and a crewed mission before the year is out.

China is estimated to spend around $6bn a year on its space programme. Although that is almost $1bn more than Russia, it is still a fraction of the American space budget, which is around $40bn a year. Despite its large budget, the US made only 19 successful space launches in 2013, compared with China’s 14 and Russia’s 31. With numbers like this, it is clear that China has arrived in space, and is set to become stronger.

“You will see the Chinese quite visibly begin to match the capacity of the other spacefaring powers by 2020,” predicts Brian Harvey, space analyst and author of China in Space: The Great Leap Forward . Key to this will be the large manned space station, Tiangong, which they plan to have in orbit by then. Although not as physically large as the International Space Station America, Russia, Europe, Japan and other countries have been building and using since 1998, China’s space station will have a broadly similar capacity to perform science.

“Science is becoming more and more important in the Chinese space programme,” says Wang Chi of the National Space Science Centre, Chinese Academy of Sciences. “We are not [just] satisfied with the achievements we have made in the fields of the space technology and space application. With the development of the Chinese space programme, we are trying to make contributions to human knowledge about the universe.”

Perhaps most impressive is the broad front on which the Chinese space programme is advancing. They are making strides in everything from human space flight to space science and planetary exploration.

So do the Chinese want to take over space? Brian Harvey, space analyst and author of China in Space: The Great Leap Forward, believes the Chinese simply want to be seen as equals. “To use a Chinese phrase, I think they are wanting to bring their own mat to the table,” he says. “They are looking for equality, they want respect from the world’s space community.”

To that end, China’s biggest inroad has been made with the ESA through the space science programme. Soon after the turn of the century. ESA launched the Cluster mission to study so-called “space weather” and the electrical malfunctions this could cause on satellites. The Chinese were keen to learn more about space weather too and came to the European agency with a proposal: they would build extra satellites to enhance the Cluster mission if ESA would collaborate with them.

“They understood that space weather was a key challenge as we rely more and more on technology in orbit,” says Christopher Carr, a physicist at Imperial College, London, who worked on the Cluster mission. ESA took care of the negotiations, allowing scientists, including Carr, to build the instruments unhindered. Although there were some differences in working methods that had to be ironed out, Carr says: “Overall it was an enjoyable collaboration.”

The Double Star mission was launched in 2003 and became China’s first scientific satellite. Cluster and Double Star have so far produced 2,300 peer-reviewed science papers. “That is an enormously successful, astonishing scientific output,” says Carr.

China has gone from strength to strength. In December 2015, it launched the Dark Matter Particle Explorer, a satellite to look for the mysterious non-atomic matter that astronomers believe makes up a large fraction of the universe. This December, it plans to launch the Hard X-ray Modulation Telescope to look for black holes. ESA and China are working together on a new mission – the Solar Wind Magnetosphere Ionosphere Link Explorer (Smile), which is slated for launch in 2021.

The Chinese know that the value of these collaborations extends way beyond the science. “We are the newcomers in space science, and don’t have much experience,” says Wang Chi. “International collaborations are the shortcut for China to catch up with the world. In addition, science, especially space science, should be the responsibility of all humans around the globe. International collaboration is the effective way to obtain the maximum science return from any space mission.”

Favata agrees: “At ESA we collaborate with all major spacefaring nations. If Smile works well it is likely to be the pathfinder for future missions.”

In stark contrast is America, where there is a blanket ban on working with China that dates back years. The most obvious consequence of this has been the exclusion of China from the International Space Station. But far from slowing the Chinese down, the cold shoulder has actually speeded them up.

Circling above us at the moment is the disused shell of China’s first space station. The eight-ton Tiangong 1 (Heavenly Palace) was launched on 29 September 2011 and hosted two three-person crews between 2012 and 2013. It is now abandoned and expected to re-enter Earth’s atmosphere some time later this year.

The Chinese will launch Tiangong 2, a second test station, next month. It will lead to a substantial orbital facility that will be in use by 2020. Known simply as Tiangong, it will be a key base for space research, with two large science modules joined together by a connecting service module.

“They can do a lot of science on it. It will have a research capacity that the ISS didn’t reach nearly as quickly,” says Harvey.

China is not planning to keep Tiangong all to itself. In June, it signed an agreement with the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs to open the station to experiments and astronauts from UN member states, specifically developing countries that find space too expensive at the moment.

And running the experiments is where China’s astronaut programme comes in. There have been just five crewed space flights since 2003, and none at all since 2013. This is deliberate. “The idea is to take a significant step forward each time,” says Harvey, “and they’re not going to cut corners in terms of safety.”

For the next decade, the Tiangong space station is likely to be the principal destination. Their crew capsule is called Shenzhou (divine vessel). It looks similar to the Russian Soyuz modules probably because the Chinese bought Soyuz technology in the mid-90s. This same agreement saw the training of two Chinese astronauts at the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Centre in Russia, who then returned to China and trained more astronauts themselves.

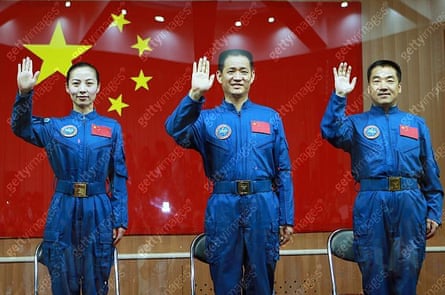

Twelve Chinese astronauts have now been into space, including Liu Yang who became the first Chinese woman in space on Shenzhou 9 in 2012. Assuming the Tiangong 2 gets to orbit in September, then Shenzhou 11 will follow on 16 October, carrying two people whose identities have yet to be made public who are scheduled to spend a month on board.

Looking to the future, the Chinese have already begun testing the larger replacement of the Shenzhou capsule. A scaled-down version flew on the June flight of the Long March 7 from Hainan. This larger vehicle will be capable of taking up to six crew to the full Tiangong space station or on missions to lunar orbit.

It was the secondary payload, Aolong 1 (Roaming Dragon), on that launch that raised eyebrows, and stoked fears in some quarters that the civilian space programme is just a front for more covert operations. Aolong 1 has a robotic arm that can grab another satellite and guide it to burn up in Earth’s atmosphere. Officially, it is to remove space debris from orbit but it could also be used as a weapon, bringing down a rival’s satellite.

Although this is true of any space debris removal system, doubts remain because China does not have an unblemished record in anti-satellite weaponry. In 2007, the Chinese shot down one of their own orbiting spacecraft in what was probably a thinly veiled warning to America. Chinese concerns had been growing since 2002 when the US withdrew from 1972’s Anti-Ballistic Missile treaty, which paved the way for President George W Bush’s administration to develop space-based weapons systems.

Since that time, concern over China’s militarisation of space has persisted in America. To others, however, that is little more than paranoia. “I think the military element in the Chinese space programme is overstated,” says Harvey. “It’s based on a misreading of the fact that their facilities are protected by the military. It’s a bit like saying the US military controlled the Apollo programme because the US navy took the returning astronauts out of the ocean. It doesn’t stand up.”

The military may not be in the driving seat, but it does launch about 15-20% of China’s space missions. The Yaogan series of satellites are billed as remote sensing missions but analysts believe they are actually spy satellites. “I suspect they are entirely military missions. I’ve never seen any scientific papers from the Yaogan missions,” says Harvey.

It is this American fear of China’s military that’s been driving the ban on collaboration, in particular the prevention of technologies being transferred to China by mistake. But now ESA has found a way to allow collaboration without the loss of control. It is “an elegant solution”, says astrophysicist Graziella Branduardi-Raymont at University College London, who is working on Smile. “China builds the basic spacecraft and sends it to Europe. ESA and its collaborators then attach the payload module, which holds the science instruments, and launches the mission. That way, no western tech goes to China.”

When it comes to rockets, China continues to develop a formidable arsenal of launch vehicles. Their rockets are called Long March and have been in development since the 1970s. The mainstay of their complement is gradually being replaced by the Long March 5, 6 and 7.

While the Long March 7 in June was capable of lifting about 13 tonnes into low Earth orbit, it is the Long March 5 that analysts are really excited about. Due to make its maiden flight this autumn, it’s capable of lifting 25 tonnes to low Earth orbit, rivalling anything the Americans, Russians or Europeans currently have. It is not yet known what the Long March 5 will send into orbit, but the giant rocket’s second flight, scheduled for next year, will be carrying a very special cargo. It will be a robotic mission designed to land on the lunar surface and send back samples of moon rock to the Earth for Chinese scientists to analyse.

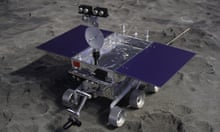

The Chinese call their lunar exploration mission Chang’e, after the Chinese goddess of the moon. In December 2013 Chang’e 3 hit the headlines after it successfully deployed a small rover on the lunar surface. Despite some technical problems, it continued to return data until just a few weeks ago.

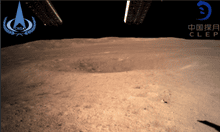

Now, China plans to land a similar mission on the far side of the Moon in 2018. This will be a world first. “The Russians did think about such a mission in the 1970s but they never got much further than paper studies. This is real, the spacecraft is already built,” says Harvey.

Also in the advanced planning stages is a rover to go to Mars. Pencilled in for launch in 2020, the Chinese Mars mission is going to find itself racing Nasa and the ESA, which have their own Mars rover missions launching that year too.

But what about a human landing on the moon? There could be no bigger sign of Chinese competency than that. Sure, America did it almost 50 years ago but with each passing year Apollo seems to have less relevance to the modern exploration of space. Nasa has held back from committing to a new round of lunar landings. Russia and ESA would both like to go to the moon but can’t go it alone. The Chinese, however, seem to have the lunar surface in their sights. Designs for a Long March 9 rocket are currently being studied. With the first launch for the Long March 9 due in 2025, China could very well be in a position to land astronauts on the moon by 2030. This puts it roughly neck-and-neck with America, which currently plans to send astronauts to lunar orbit in 2023 but which has made no commitment to returning to the surface.

Almost certainly this will be a flashpoint, but the ignition of a new space race would be a mistake. The Apollo programme of the 1960s cost the equivalent of hundreds of billions of dollars for little more than technological one-upmanship. Better now, surely, to cooperate, spreading the cost and the benefit across the world.

The Chinese space programme is gaining momentum year upon year. Its power lies not in unlimited funds but in carefully chosen projects, and the pursuit of clearly targeted goals – something the traditional space powers could learn from, especially when is comes to the crewed programmes.

At present there is no agreement on what to do when the current agreements to use the International Space Station come to an end in 2024. With America continuing to talk about hugely expensive missions to Mars, but with no real plans or budget in place to do this, Russia and ESA could increasingly find that their space ambitions are more aligned with those of the Chinese.

What is clear is that the Chinese space programme is more willing than ever to cooperate. With the signing of the UN agreement to host foreign experiments and eventually astronauts on their space station, the Chinese are opening up. It is of course hard to imagine Russia and in particular ESA abandoning Nasa altogether, but it is not inconceivable. In the aftermath of 2008’s credit crunch, Nasa pulled out of a number of high-profile joint missions with Europe, including robotic Mars exploration and space-based observatories. This left ESA floundering for new partners, or frantically rescoping its missions. Increasingly, China will play a role in the international exploration of space, and although it is early days they have so far they have proved to be highly reliable.

A seismic shift in space power is taking place. Europe could pivot either way or balance in the middle. Although most still talk about China “becoming” a space superpower, it is likely that history will record the tipping point as 25 June this year, when a giant rocket split the sky amid the cheers of more than 20,000 tourists.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion