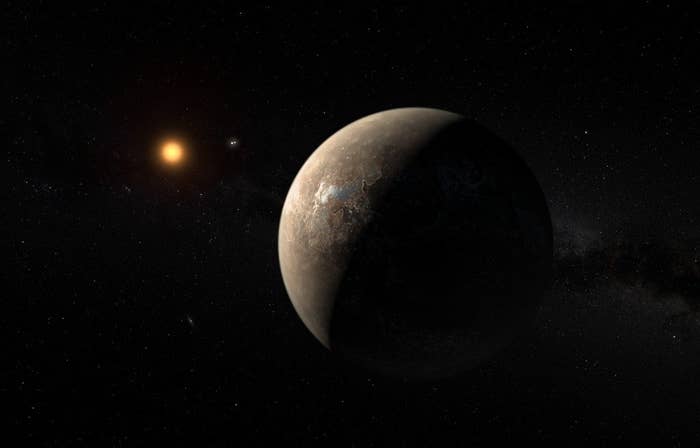

A planet roughly the size of Earth that may have liquid water – and could theoretically support life – has been found around our nearest star.

The small, rocky planet orbits Proxima Centauri, just 4.2 light years away. It could be as little as 1.3 times the size of our own planet, and is at the right distance from its star for liquid water – neither so far away that it will freeze, nor so close that it will boil.

A German magazine printed rumours about the discovery last week, but the study has now been published in a paper in Nature. The study's authors have told BuzzFeed News that they have been in touch with a team, led by Professor Stephen Hawking, that had planned to send a mission to a different star, but could now make Proxima Centauri the target.

Professor Lewis Dartnell, an astrobiology researcher at the University of Westminster who was not involved in the study, told BuzzFeed News that the discovery was "absurdly exciting" and "could usher in a whole new phase of exoplanet explorations", possibly including sending robots, such as Hawking's planned mission, to study it. However, he warned that there are reasons to be cautious about whether "Proxima b", as the planet is known, is suitable for life.

Proxima Centauri is a red dwarf star, much smaller, older, and cooler than our sun. It's too small and dim to be visible to the naked eye. Scientists at Queen Mary University of London spotted using powerful telescopes that the star appeared to "wobble" slightly. When a star wobbles regularly, it often means that there is a planet orbiting it, pulling it back and forth with its gravity.

Scientists are able to detect it because the light from the star changes colour very slightly as it moves towards us and away again – just as the sound from an ambulance siren gets higher as it comes towards us and lower as it goes away again. The movement is tiny – Proxima Centauri moves away from us at only about 5km (3 miles) an hour, and then towards us at the same speed. But it was enough to spot.

The star has been studied for more than 15 years, ever since hints of a planet around it were spotted in 2000. However, confirming the planet's existence was complicated. "It's a very active star, a flare star," Richard Nelson, a professor of astronomy from Queen Mary's who worked on the study, told BuzzFeed News. "It's common among these small, low-mass stars." Solar flares fire huge amounts of gas into space, and move the star slightly. That makes it much harder to detect the regular signal of an orbiting planet in all the random noise of solar flare movement.

Between January and March this year, the Queen Mary's team used two major telescopes at the European Southern Observatory in Chile to study Proxima Centauri for 60 days. Proxima b only takes 11 days to orbit its star, so they were able to observe several orbits. "The statistics look very good," said Dartnell. "It was very noisy data but they've done enough to pull out the signal and show that it is in fact due to an orbiting planet."

Because it's got such a fast orbit, the researchers know that Proxima b is very close to the star – just one 20th of the distance from Earth to the sun. It could still be the right temperature for liquid water to exist, because the star is so cool, but being so close has other implications for whether life can exist.

For one thing, the star is very active, regularly launching solar flares – and therefore radiation – into space. "It receives 10 to 100 times more X-ray and ultraviolet radiation than Earth does," said Nelson. "That can have an impact on the atmosphere and oceans, if they're there. If there wasn't very much, they could have evaporated."

For another, when a planet is very close to a star, it can become "tidally locked", so that one side always faces the star – just as we can always only see one side of the moon. "The problem with a tidally locked planet is that you have one side in everlasting day, the other in eternal night," said Dartnell.

That means that there's a stark difference in temperatures between the two sides. Depending on how thick the atmosphere is, there could be enough wind to move the heat around, but if there isn't, the dark side could be cold enough for carbon dioxide to freeze, said Dartnell. "The debate over whether life could exist on tidally locked planets is absolutely raging," he said.

Nonetheless, it appears to be the most likely candidate for finding life. "This is without a doubt the most habitable-looking planet we know of in our local neighbourhood," said Nelson. "There have been many observations of rocky planets but they’re mainly very distant. In astronomical terms, this is extraordinarily close."

The next stage, he says, is to train the Spitzer space telescope on it. If Proxima b happens to pass in front of the star, it will be possible to tell exactly how big and how dense it is. And with another telescope, the James Webb, which is due to launch in 2018, it may be possible to tell what its atmosphere is like, using a technique called spectroscopy.

"If you see the signature of oxygen and methane, that would be exciting," said Dartnell, "because the only way we know about oxygen being pumped out in large amounts is photosynthesis. We'd know that there’s not just an Earth-like planet but there’s good evidence that there might be life."

But the most exciting possibility is that we could send robot representatives to it. In April, Hawking and Yuri Milner, a Russian billionaire, announced a project called Breakthrough Starshot. The plan is to launch thousands of tiny space probes, each with a thin sail. They would be powered by a laser fired from Earth, and would accelerate slowly up to 20% of the speed of light. That could get a spacecraft to Proxima Centauri in about 20 years – compared to roughly 80,000 years for our fastest chemical rockets.

Hawking and Milner planned to aim the launch at Alpha Centauri, a pair of stars very close to Proxima Centauri. However, Nelson believes that the Proxima b discovery could change their minds. "There has been some contact between us and the Breakthrough Starshot team," he said. "I think they're quite interested in changing their target."

Solar sails "are the sort of technology we understand today", says Dartnell. "It's not crazy sci-fi stuff like warp drives. It's stuff that we could conceivably launch in a few decades."

Nelson agrees: "Certainly the spacecraft won't get there in our lifetime. But the engineering could begin in our lifetime – maybe they could even be launched in our lifetime."