Europe and Russia delay ExoMars rover project to 2020

- Published

As expected, the European and Russian space agencies have delayed their next mission to Mars from 2018 to 2020.

It is a decision that has been well telegraphed in recent months, with both agency officials and industry chiefs expressing their doubts that all the hardware could be made ready in time.

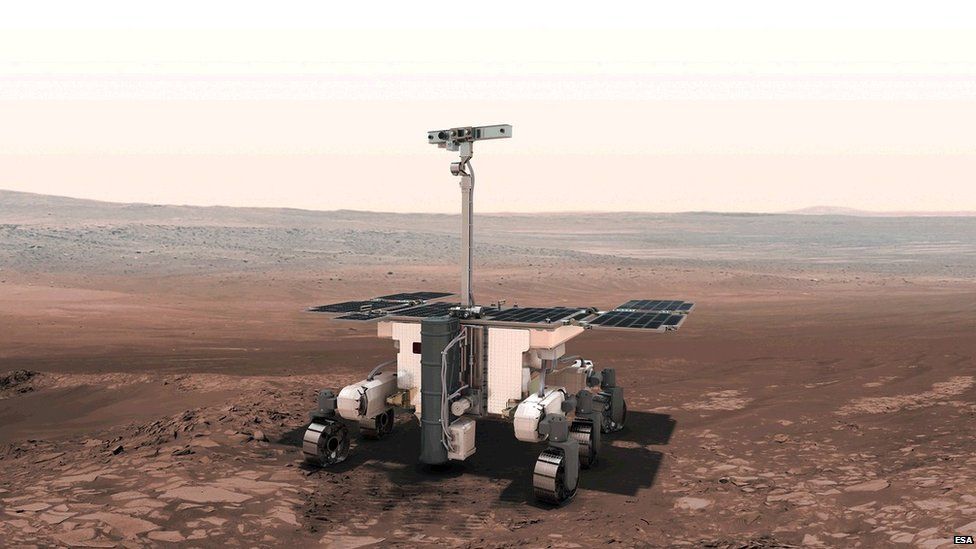

The aim of the mission is to land a rover on the Red Planet.

Capable of drilling up to 2m below the surface, it would search for signs of past or present life.

It is the second part of the so-called ExoMars programme. The first part - a satellite to study the atmosphere of the planet - was launched successfully in March and should arrive in October.

But the surface robot will now follow four years behind, instead of two (planetary alignment dictates that the most efficient launch opportunities become available at 26-month intervals).

The announcement of the launch slip was issued by the European Space Agency (Esa) on Monday.

Russian engineers have been struggling for a while to keep their design for the vehicle's landing mechanism on the 2018 timeline, and in Europe, too, some components and instruments were considered to have very little margin in their development schedule.

A "tiger team" set up by Esa and the Russian space agency (Roscosmos), and which included European and Russian industries, could find no solutions to recover lost time.

Rolf de Groot is head of Esa's Robotic Exploration Coordination Office. He told BBC News: "It is not only the components of the spacecraft; it's several of the instruments.

"What we have been doing lately is seeing if we could shorten the assembly, integration and testing (AIT) phase to something that would be acceptable from a risk point of view, but still make the 2018 launch.

"Very recently, we have concluded that this is not possible without adding a large amount of additional risk to an already risky mission. So, we decided the only responsible thing to do was move to the 2020 launch date."

For European scientists and engineers who have been working on the rover concept, such delay has become part and parcel of the endeavour.

First envisaged as a small technology demonstration mission, the robot vehicle was approved by European nations back in 2005, with a launch first pencilled in for 2011.

Then, as ambitions grew and the design was beefed up, the start date was put back. At first, it was shifted to 2013, but further problems saw slippage to 2016, and then again to 2018.

At the root of the ExoMars rover's problems has been the lack of a full and proper budget to carry it through. At one stage, in 2009, Esa decided to join forces with America to try to make it happen, only to see Nasa walk away three years later when its priorities changed.

That could have killed the project there and then, but for an offer from the Russians to fill the partnership position vacated by the US.

Nonetheless, as events have now shown, there has been insufficient time to recast the mission.

And the money issue has not gone away. Indeed, it now becomes a bigger problem.

Already, there is a shortfall in the required budget for the rover on the European side. With the additional delay of two years, this deficit only increases.

Esa and the two biggest European space companies - Thales Alenia Space and Airbus Defence and Space - are in the final stages of agreeing a price to build rover. They are at odds over the figure in euros, but the aim is to get the negotiations done before a meeting of member state delegations in June.

It is at this council gathering that Esa officials will set out a new path for the project. One intention is to continue apace with European preparations, and then store all hardware for a year before the last stages of AIT. This would mitigate some of the additional costs that come from maintaining large teams.

The two nations most invested in ExoMars are Italy and the UK, with Britain charged with assembling the rover.

Airbus Defence and Space has recently built a cleanroom at its Stevenage facilities north of London to perform this task.

If there is one positive to come out of the delay it is that the list of potential landing sites will now lengthen.

The particular flight parameters of a 2019 arrival at Mars limited the rover to really only one destination - Oxia Planum.

An arrival two years later opens up the possibility of reaching other targets of high science interest.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos

- Published14 March 2016

- Published25 November 2015

- Published21 October 2015

- Published24 May 2015