A New Global Swarm of Weather-Sensing Satellites

Armed with tiny orbiting sensors, a startup plans to build the world's largest database of private weather data.

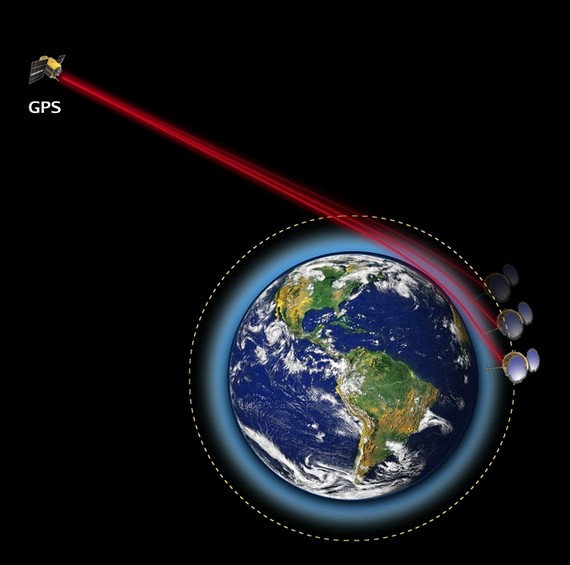

Every bird, every bug, every human being on Earth is enveloped at all times by the signals of the Global Positioning System (GPS).

Its 32 satellites, operated by the U.S. government, do far more than just tell you where you are. GPS keeps the time on cellphones in-sync. It helps prevent shark attacks. It monitors earthquakes. It’s even used in college-football training.

And now, a startup plans to use it to track the weather.

On Thursday, a San Francisco-based company called Spire announced its plans to deploy 20 tiny satellites into low-Earth orbit. It hopes to generate a private database of global weather data, which it believes will rapidly become the world’s largest.

“This satellite data system will provide five times more [weather] data than the world has today by the end of 2015,” it says in a release.

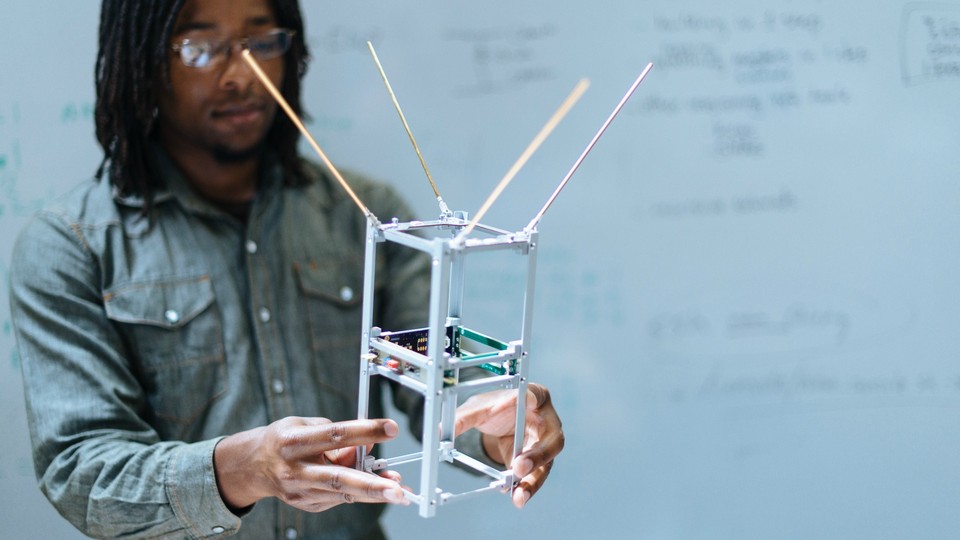

Eventually, Spire plans to operate 125 orbiting sensors. Like other new satellite startups, it plans to use many Cubesats—cheap, shoebox-sized nanosatellites that linger in the upper atmosphere for about two years before burning up—instead of one or two big orbiting machines.

Unlike many other competitors in the space, though, its satellites will have no camera. Instead, they’ll sense the weather by a technique called GPS radio occultation. Here’s how that works: When GPS signals hit the Earth at a tangent, they’re distorted by the atmosphere before continuing on their (new, slightly adjusted) way. By monitoring these distorted signals, Spire’s Cubesats can figure out the conditions of the atmosphere that did the distorting. Specifically, they can calculate the temperature, pressure, and wetness of the troposphere—in other words, the main meteorological variables of the part of the atmosphere where we live. (In other-other words, the weather.)

In particular, the company plans to monitor parts of the Earth it believes are currently underserved by big governmental satellites—like the oceans. Spire’s pre-existing business is in tracking cargo ships and illegal fishing vessels, so it’s already adept at looking at the seas.

The company also plans to augment U.S. weather data, in case a government weather satellite fails, as a recent report predicted it might.

What strikes me about Spire is how much it relies on public systems. Not only GPS, but also the initial studies that invented GPS radio occultation, were funded with U.S. government money. When I talked to Peter Platzer, Spire’s CEO, he seized on this.

“We stand on the shoulders of giants,” he told me. The company has “a tremendous appreciation of what has been done.”

In fact, he said, he created the company’s business model and contracting scheme to allow for Spire data to be shared between governments and distributed to citizens, similar to how public weather data is treated today.

“Maybe because I’m European,” he said, he believes in the “human birthright of having protection from extreme weather events.”

He compared Spire’s role to SpaceX: Just as governments could offload repetitive tasks to private agencies who could make them cheaper by focusing exclusively on them, the government could eventually add private weather data to its own collection.

And perhaps so: Spire, he said, has already signed letters of intent to purchase from international governments and companies. Its first satellites will launch later this year.